← Back

Very young green turtles go into the Sargasso Sea

The life of young (“lost years”) marine turtles had long been a mystery. Improvements in satellite telemetry now enable to unveil part of it. North Atlantic young green turtles, in particular, seem to actively favor the Sargasso Sea and its natural accumulation of Sargassum algae.

Tracking animals’ early life

Fast-growing species like young marine turtles are hard to track in their first year(s) of life. Attaching a PTT to them in a way that won’t hinder their movements, nor their growth, is complicated. Moreover, if their growth means molting or equivalent, externally glued tags may fall off the animal. The tag must also be lightweight and not overpower the small animals. Solar charging tags are usually not used to power tags on marine species since they won’t be exposed to air and the sun long enough to recharge the tags or transmit to overhead satellites.

A number of assumptions have been made about the early years marine turtle spend offshore in the open ocean as part of their “lost years”. They are thought to swim off the continental shelf after hatching, and stay in the open ocean, swimming or drifting within the main ocean currents, for several years. There, they are supposed to associate with floating habitats, including Sargassum algae.

Novel use of bird tags for turtles

However, today, improvements in tags and in attachment methods enable researchers to equip very young marine turtles with satellite tags for the first time by researchers at the University of Central Florida. Twenty-one young green turtles (Chelonia mydas) of more than 300 g and 12 cm (up to 19 cm) in shell length were equipped using solar-paneled 9.5-g bird tags, pressure-proofed and glued on the top of the turtle shell.

Since the young turtles live mostly at the sea surface, the tags receive enough sunlight to power the tags for tracking. Experiments showed that the tags can remain attached to the turtles and transmitting for some time. Indeed, the 21 green turtles were tracked for a period between 10 and 152 days (66 days on average).

Sargasso Sea as a green turtle nursery

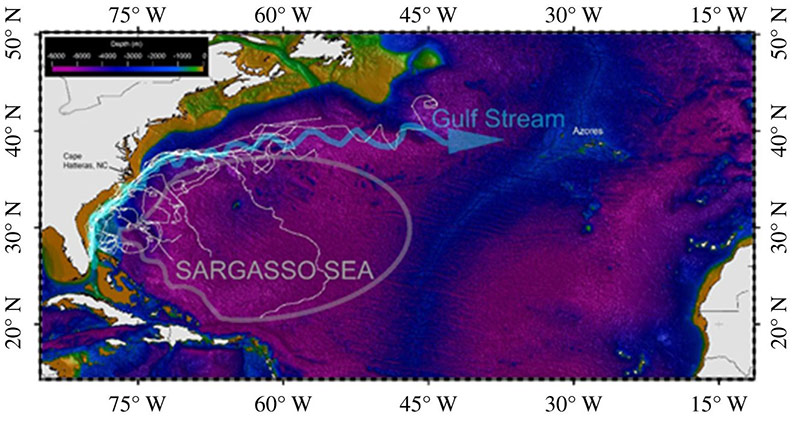

Over half the turtles in this study left the Gulf Stream current around Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (USA) and traveled to the Sargasso Sea, at the center of the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre. This work shows that the juvenile turtles may not remain in the Gulf Stream current, but may actively swim and orient—versus the old belief that all young turtles would passively drift in the currents.

For young green turtles originating from the Atlantic US coast, he Sargasso Sea seems to be their destination. Newly hatched green turtles have been observed to select and use the Sargassum by perching on top of the floating algae or burrowing into the mats. In the end, two-third (14 of 21) of the tracked juvenile green turtles ended up within the Sargasso Sea when their tag stopped transmitting.

Thus Sargasso Sea waters and their algae mats seem to play a role in the early life cycle of green turtles in the North Atlantic. An earlier study conducted with young loggerhead turtles led to a similar conclusion with respect to the Sargasso Sea but with noticeable differences in the turtles’ time spent within the Gulf Stream (longer for loggerheads). The assumption that all marine turtles behave similarly after hatchling should thus be checked with dedicated studies, in the different populations around the Earth.

A number of questions are still unanswered, such as how long the turtles are spending in the Sargasso Sea, do the individual’s fitness play a role in the direction they take or the fact they are carried by the current, etc. Moreover, since the center of the ocean gyres are places where plastic debris are also accumulating, this could also be an additional threat to the young turtles.

Protection in this crucial region for marine turtles’ development would be in order, even though it is mostly within international waters. Other similar studies in the different subtropical habitats of marine turtles, and among the different species are needed.

Animated movements of all green turtles released and tracked in 2012 (April 2, 2012 to July 31, 2012). Each purple dot represents an individual turtle. Sea surface temperature is overlaid on the map with warmer colors representing warmer waters. Purple dots disappear when a turtle’s tag ceased transmissions. (Animation created by Dr. Jiangang Luo, University of Miami, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science)

Animated movements of all green turtles released and tracked in 2013 (December 16, 2012 to April 14, 2013). Each purple dot represents an individual turtle. Sea surface temperature is overlaid on the map with warmer colors representing warmer waters. Purple dots disappear when a turtle’s tag ceased transmissions. (Animation created by Dr. Jiangang Luo, University of Miami, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science).

Acknowledgment

All research was completed in full compliance with protected species laws and guidelines of the United States and State of Florida, specifically: FAU IACUC protocol A08–40; Florida Marine Turtle Permit MTP-073; and US Fish and Wildlife Service Permits USFWC-TE05127–2.

Reference & links

- Mansfield KL, Wyneken J, Luo J. 2021 First Atlantic satellite tracks of ‘lost years’ green turtles support the importance of the Sargasso Sea as a sea turtle nursery. Proc. R. Soc. B 288: 20210057. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.0057

- Twitter/Instagram: @UCFTurtleLab

- Web: https://sciences.ucf.edu/biology/marineturtleresearchgroup/

Main Photo: Young (“Oceanic stage”) green sea turtle released with solar-powered satellite tag in Sargassum habitat. (credit: Gustavo Stahelin, UCF MTRG; Permit number NMFS-19508)