← Back

Western Australian green turtle behaviour analysed

A large population of green turtles is found in Western Australia. Using a database of tracks enables scientists to model their behaviour and help in deciding the protection regulations to enforce.

The green turtle (Chelonia mydas) is a highly migratory species of marine turtle. This species is found all around the Earth’s tropics. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists it as endangered. At the same time, the species is considered as “vulnerable” in Australia, where some of the largest rookeries of the Indo-Pacific region are found. Many of those turtles are in Western Australia, where there is increasing hydrocarbon and mineral resources exploitation activities.

Completing a green turtle tracking database to model their behaviour

The potential impact of these activities on threatened species has already led to a number of satellite marine turtle tagging projects in Western Australia. Indeed, seventy-six green turtles were tagged in this region between 2001 and 2018 during the breeding season (October to April). The PTT were either Argos-only locations, or both Argos and GPS. Based on these existing data and on the locations of the main rookeries, areas where new deployments should be undertaken were identified. Twenty more green turtles were thus equipped and tracked.

More info about animal tracking with Argos

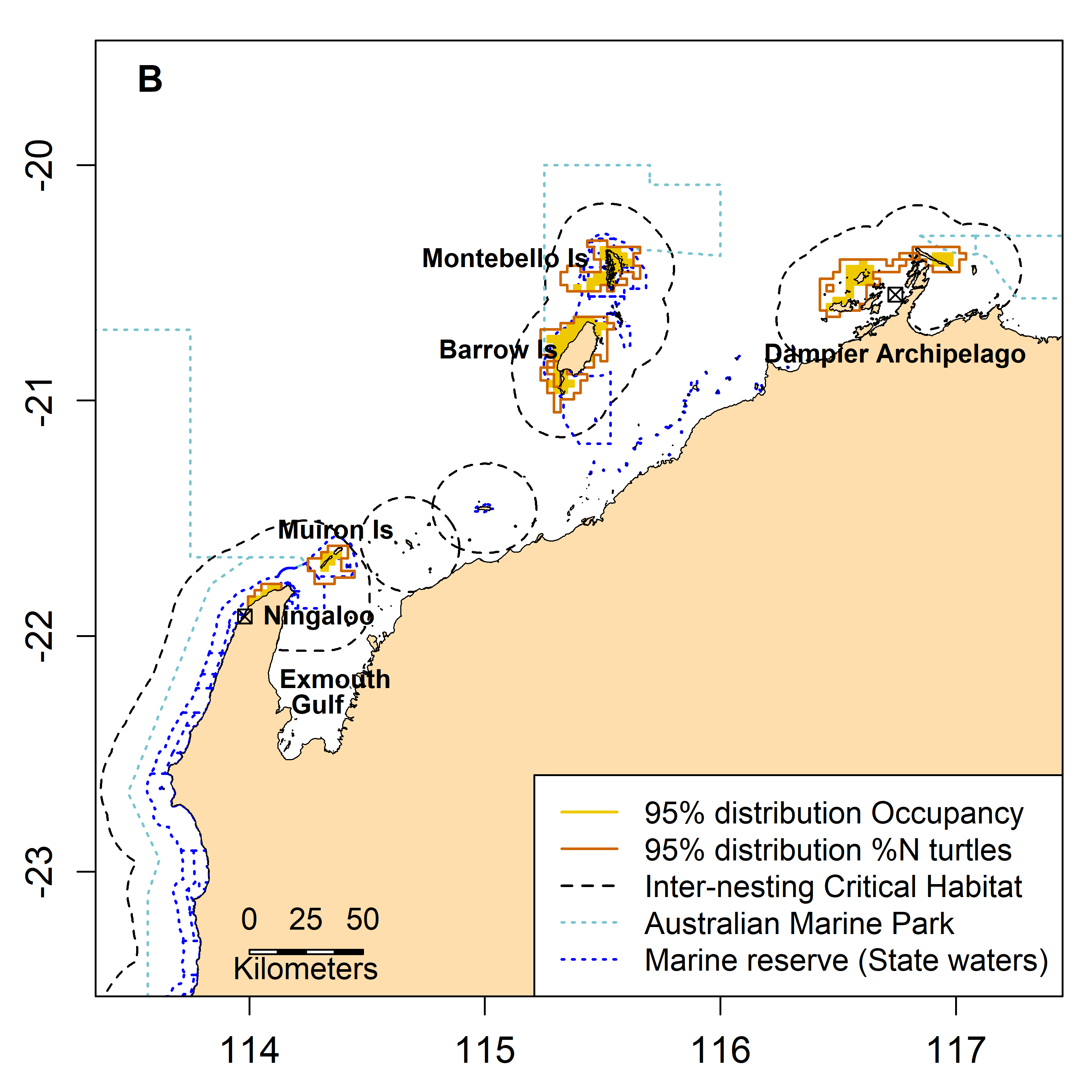

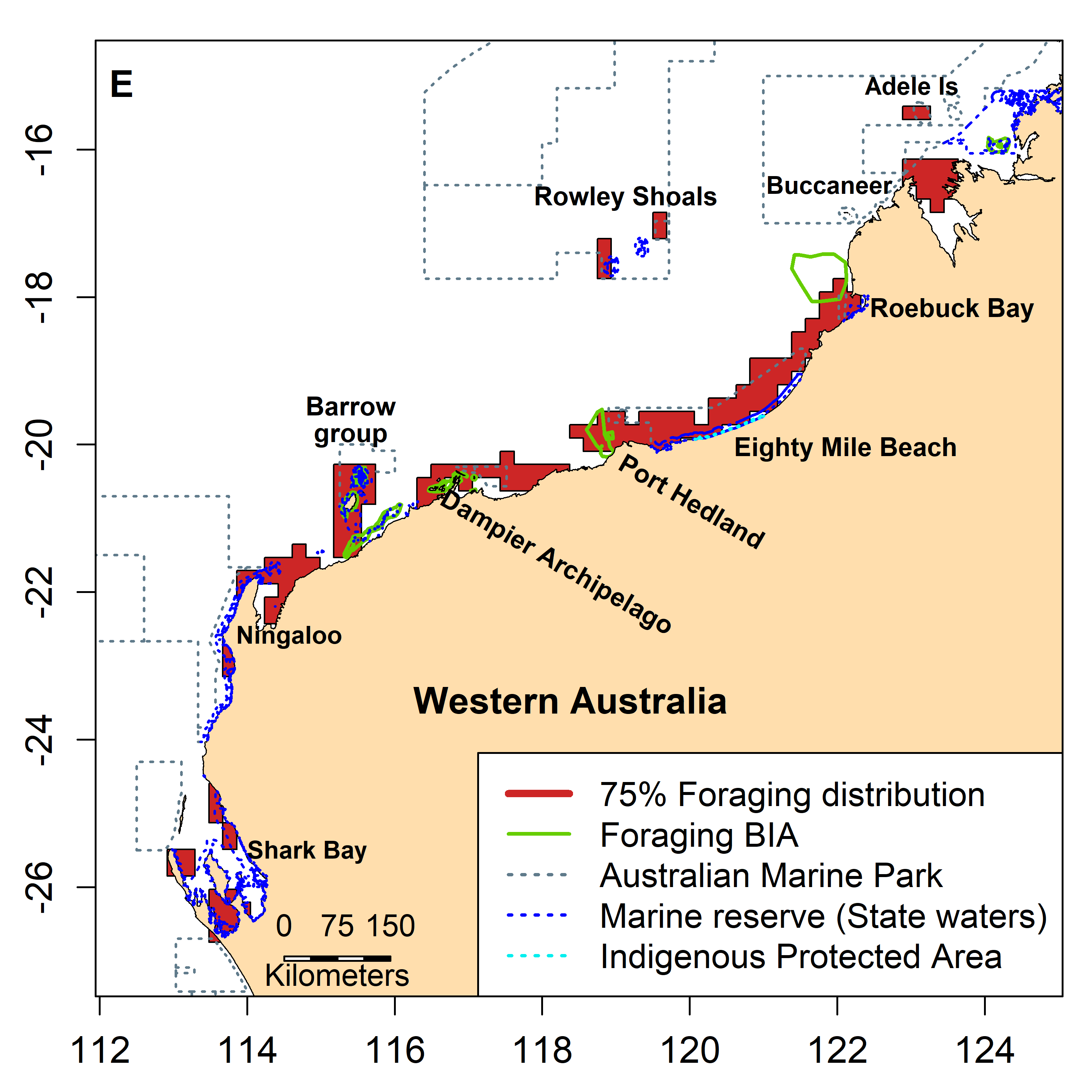

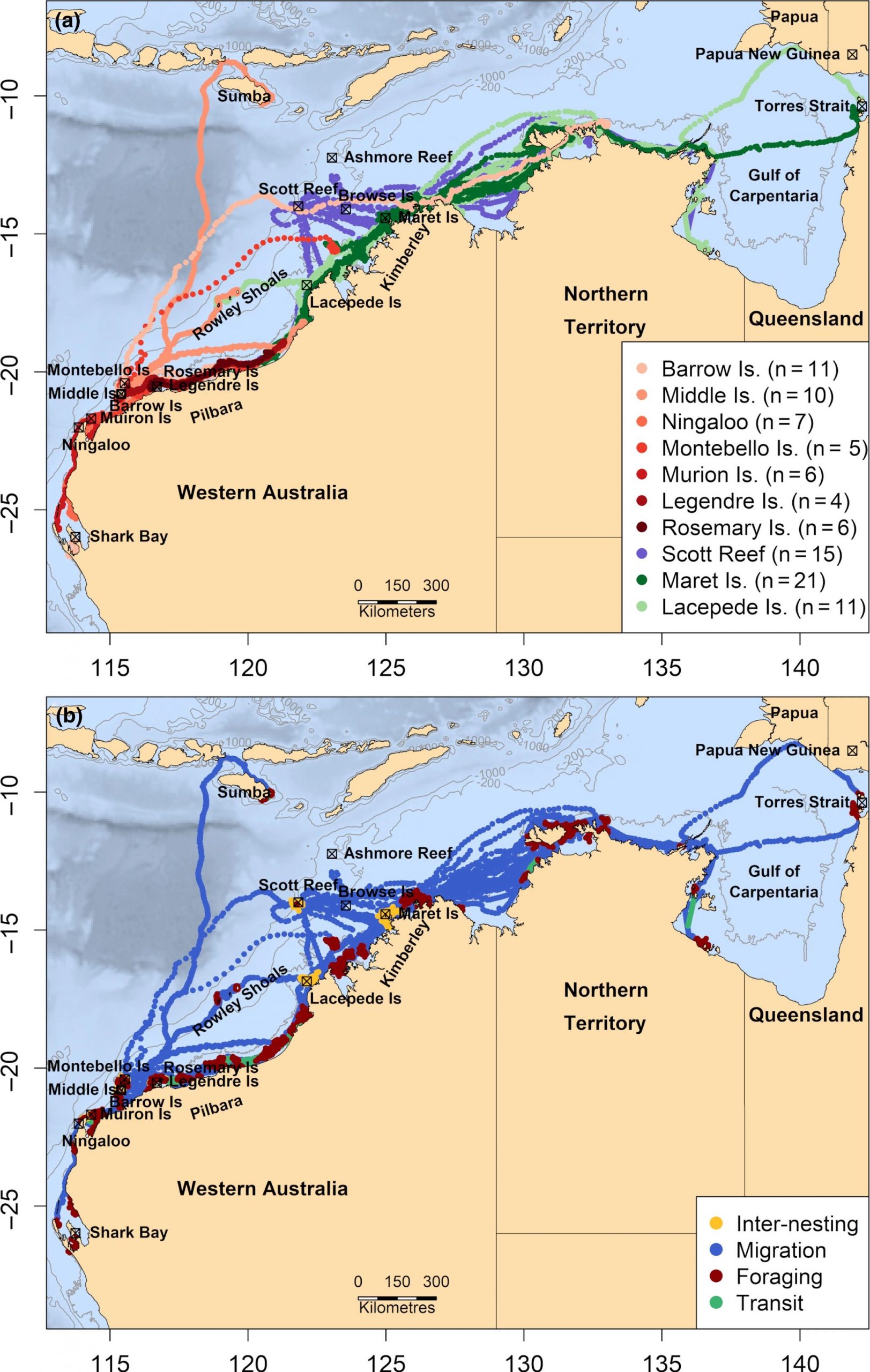

All the satellite tracks used in the analysis (a) coloured by stock/substock and (b) coloured by behaviour mode. The 50, 200 and 1,000 m depth contours are shown in light grey (from [Ferreira et al., 2021])

This leads to a total of 96 adult, female green turtles tracked from ten rookeries and two genetic stocks during both the inter-nesting (individuals moving at sea during the nesting season) and post-nesting periods. Compiling and analysing such a large tracking dataset allowed to have a representative sample to model the spatial distribution and behaviour of the population.

Analysis of nearly hundred tracks

The model enabled to identify two main migratory corridors (Pilbara and Kimberley). In contrast with other populations around the globe, green turtles in Western Australia do no migrate as far (about 800 km), or even do not migrate at all for 14%. When migrating they keep mostly to the coasts, a behaviour which is also observed in the populations of the Mediterranean Sea, Equatorial Guinea and Costa Rica, possibly linked to foraging. Some large distances (over 2,000 km) and open ocean movements were however recorded.

Foraging grounds are distributed over a broad area, and scarcely overlap. But this might be due to the shear size of the area, and to the (relatively) small sample used, with respect to the whole local green turtle population. Deploying transmitters not only in nesting areas but also in foraging ones might help to better qualify this behaviour, and enlarge the population sampled to males and juveniles.

Results show that the currently regulation of a 20 km radius protected area around rookeries should be effective in protecting nesting green turtles in Western Australia in most cases. But the current spatial protection of foraging grounds is still underestimating the area used by turtles.

Reference & links

- Ferreira LC, Thums M, Fossette S, et al. Multiple satellite tracking datasets inform green turtle conservation at a regional scale. Divers Distrib. 2021;27:249–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13197

- Online resource with maps: https://northwestatlas.org/nwa/nws2s-megafauna

- Northwest shoals to shore project: https://www.aims.gov.au/nw-shoals-to-shore

Main photo: a green turtle with an Argos PTT going back to the sea after nesting (credit Luciana Ferreira/AIMS)