← Back

Understanding Catastrophic Breeding Seasons in a Large Colony of King Penguins

King penguins breed on a few colonies spread around the Southern Ocean. Some years are more successful than others in that respect, and understanding why could help in protecting such threatened species. Argos can help in better assessing the reasons.

King penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) have the longest breeding cycle among penguins. They take about 13–14 months to fledge a chick, alternating between an adult being present or not. Adults leave the chicks unsupervised to fast during winter, before coming back in spring and resume provisioning, while the next brood incubation has started.

Breeding seasons can be more or less successful, but some are catastrophic. Two such cases occurred in one of Kerguelen archipelago colony two years in a row (2009 and 2010).

Use of telemetry data to investigate king penguins’ colony breeding failures

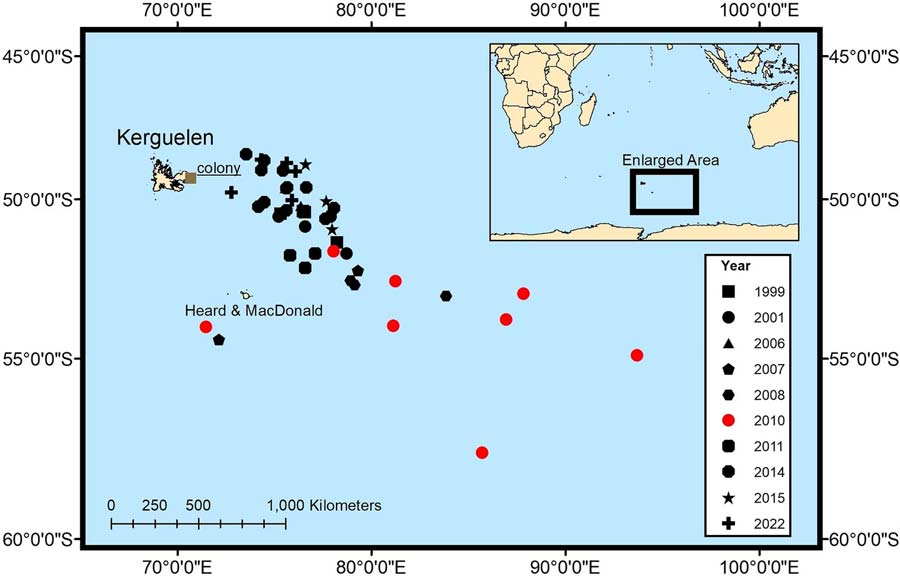

Some rearing adult king penguins in this colony have been equipped using Argos PTTs or data loggers since 1998 and up to these days (depending on the years), i.e. 24 years, with a total of 161 GPS/Argos-equipped birds, 173 depth-logger-equipped birds.

This, and on-site monitoring of chick mass, date of arrival of the adults or colony counts enabled to compare the anomalous years with “normal” between 1998 and 2022.

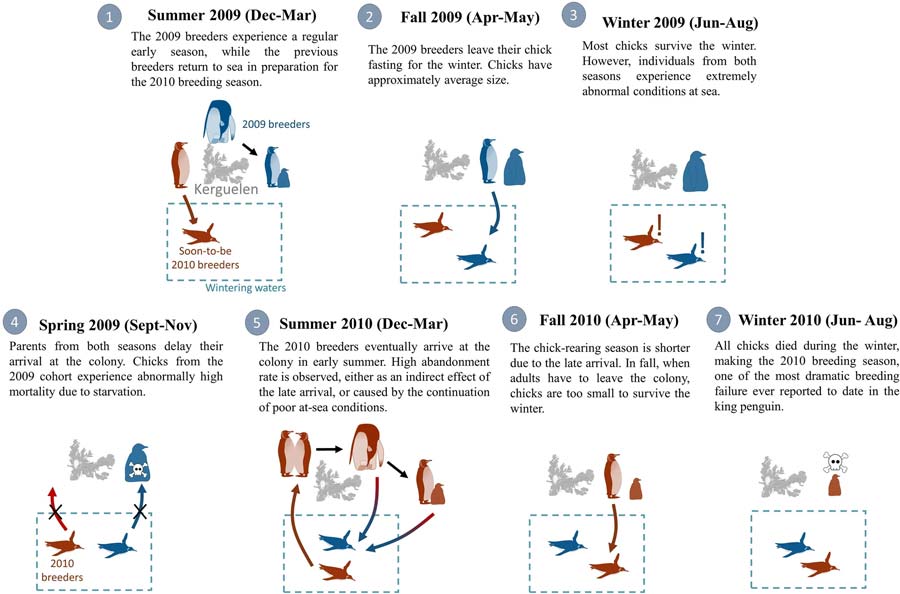

Tracking and diving data of the adult king penguins showed that foraging effort appeared to be normal in 2009 in terms of foraging trip distance, trip duration, and dives per day. The conclusions on foraging success were similar: dive wiggles per day, which is a proxy for prey pursuit, and mass gained per day were not statistically different than other years. Chick mass before winter (April), chick survival in mid-winter (July) were lower than average, but not unusually so.

Afterwards, though, chick survival decreased drastically between mid-winter and the following spring (October), with survival not exceeding 6%, the lowest of the observed years except for 2010. Almost all chicks had died by November at what should have been the onset of 2010 breeding season seeing the return of adults.

Those, however, arrived late, with a delay of several weeks. The hypothesis is that adult king penguins experienced very poor foraging conditions in winter, which affected their timing of return to the colony and thus the chick feeding, and delaying egg laying of 2010 breeding season. No environmental variables showed extreme values during the winter of 2009, which leaves few clues as to what exactly could have caused the poor foraging conditions.

Second bad year in a row for king penguins’ breeding

By February 2010 the numbers of king penguins were seemingly normal in the colony, though no breeding count could be undertaken. Trip duration and foraging distance were longer in 2010 than all other 9 years with available telemetry data during incubation, and foraging seemed much more difficult (lower dives and dive wiggles per day).

Nearly all monitored pairs (93.8%) abandoned their egg during incubation period (none of the monitored pairs over the eight other years with similar incubation data did). This might be a consequence of the late arrival of the adult king penguins, or a continuation of the reasons behind the 2009 winter poor foraging conditions.

Winter thus could have a large importance on reproduction success for species like king penguins which breed in few large colonies. These events highlight the need for more research and data on such marine top predator in winter, taking into account environmental data, prey and foraging success.

Reference & link

- Brisson-Curadeau, É., A. Scheffer, P. Trathan, F. Roquet, C. Cotté, K. Delord, C. Barbraud, K. Elliott, C.-A. Bost, 2023: Investigating two consecutive catastrophic breeding seasons in a large king penguin colony. Sci Rep 13, 12967 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40123-7

- https://www.cebc.cnrs.fr/