← Back

Estimating where pop-up tags surfaced to better track Bering Sea crabs

![Pop-up-Argos-tag-attached-to-a-male-red-king-crab Pop-up Argos tag attached to a male red king crab (from [Nault et al., 2024])](https://www.argos-system.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Pop-up-Argos-tag-attached-to-a-male-red-king-crab.jpg)

Red king crabs can be tracked using pop-up tags which release and surface after a scheduled time. However, once at the surface, they may not be located immediately, which introduces an important uncertainty on their location estimate, especially with respect to the proportionally short travel of the crabs. A method to correct this drift is proposed by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands Shellfish Research group.

Red king crabs (Paralithodes camtschaticus) are the largest king crabs, living along continental shelves of the North Pacific and Arctic Oceans (and now North Atlantic). Their Bering Sea population has seen a steady decline since the early 2000s ultimately resulting in recent fishery closures.

As the individuals do not move very fast, nor far, fine-scale patterns are needed to better understand the species and protect it. We saw that crabs, even deep-sea ones, can be tracked (see https://www.argos-system.org/deep-sea-crabs/), but that retrieving their exact locations is not trivial, since the pop-up tags used would drift between release and detection. The discrepancy is crucial for crustaceans moving over ranges of tens of kilometers at the utmost, more than for fish or other long-traveling species usually tracked by these devices.

Pop-up tags often drift on the surface for some time before a first location estimate is obtained. And, typically, an even longer time passes before a high-quality Argos location estimate can be computed (Note from the Editor: the launch of the Kineis constellation will shorten these delays in the future with a constellation of 25 satellites once fully deployed). When the questions are about animals’ movements of several kilometers, such drifts are a definite concern.

More info about animal tracking with Argos

Tracking red king crabs and correcting pop-up tag surface drifts

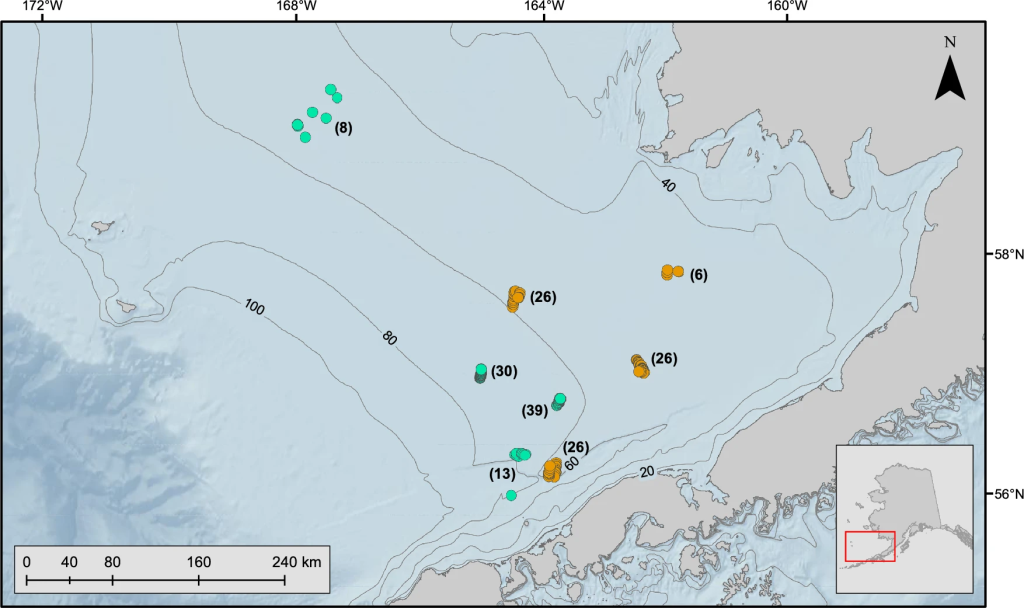

A study by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game used pop-up tags deployed on known fixed-position moorings in Bristol Bay (4 tags in 2020, 20 in 2021) and Marmot Bay (12 in 2022), Alaska (USA) to estimate and validate the location of tag surfacing. Other tags were deployed on mature male red king crabs in Bristol Bay during 2020 (84 individuals) and 2021 (90), scheduled to release in mid-October 2020, early January 2022.

The fixed moorings were selected to be close to the crabs’ equipment sites and scheduled for releases at the same time. This enabled to compare tag drifts from known positions (location uncertainty) to the distances moved by red king crabs. Both the crabs and the fixed moorings in Bristol Bay were at depths of less than 80 m with slow underwater currents, which limited the vertical drifts during surfacing.

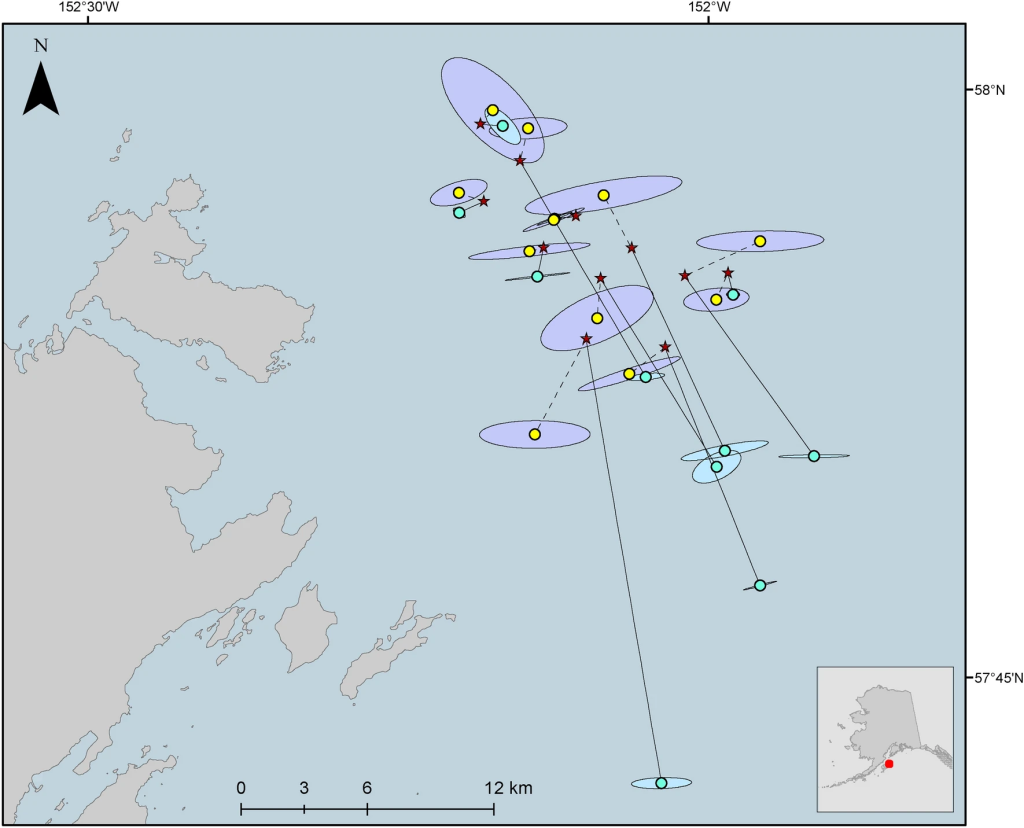

Horizontal drifts were estimated either by using the Argos-reported locations and error ellipses from the tag of interest or from a nearby tag drifting at approximately the same time. The error ellipse for the estimated location of where the tag surfaced was a combination of Argos error ellipses.

Estimating surfacing locations

For the fixed position pop-up tags, a mean distance between the estimated location and the fixed position was 2.0 km. The fixed tag positions were further compared with the combined Argos error ellipse estimates which either encompassed the tag’s fixed position or their boundaries were a mean distance of 1.3 km from the fixed position. The estimated location was on average 5.7 km closer to the tag’s fixed position than the first high-quality Argos location estimate.

The estimated drift for the tags on red king crabs prior to a high-quality Argos location estimate ranged from 4 to 21 km on average depending on the year (possibly due to a strong weather system in 2021), while the estimated displacement of the crabs was around 45 km on average. This reinforces the need of drift correction especially with turbulent surface conditions possibly limiting message reception.

The method of estimating the drift by using neighboring pop-up tags seemed to better handle extended drifts but supposes that the equipped animals stay close by and that a number of tags are used and scheduled to be released at the same time, which may not be the case in all studies.

Reference

Nault, A.J., Gaeuman, W.B., Daly, B.J. et al. Estimation of pop-up satellite archival tag initial surface position: applications for eastern Bering Sea crab research. Anim Biotelemetry 12, 7 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-024-00360-7