← Back

Tracking juvenile northern gannets: post-fledging movements and migration journeys

Juvenile northern gannets fledge independently from their parents. They are therefore required to learn flight and foraging skills and make an autumn migration on their own. Mortality in seabirds is high during their first year but when and why this mortality occurs is not well understood. Tracking juvenile gannets at the same time as adults enables us to better understand the risks to this species at different life stages.

Northern gannets (Morus bassanus) are large seabirds that breed at colonies around North Atlantic coasts, both European and American. Populations are stable, or even slightly increasing. With no natural predators, they can take a wide range of prey and travel long distances to find food. Birds from European breeding populations migrate south in autumn travelling as far south as West Africa.

Adults leave juveniles at the colony so juvenile birds must fledge and then learn flight and foraging skills before making the migration journey independently of their parents. Their first flight is made by launching themselves from their native cliff, a rather drastic technique. Ringing studies have shown that juvenile gannets can, like adults, migrate to West Africa but little is known about their journeys.

Photo of a juvenile with an Argos PTT, just (barely) visible at the tip of its tail feathers (credits Keith Hamer)

Tracking of juveniles and adults

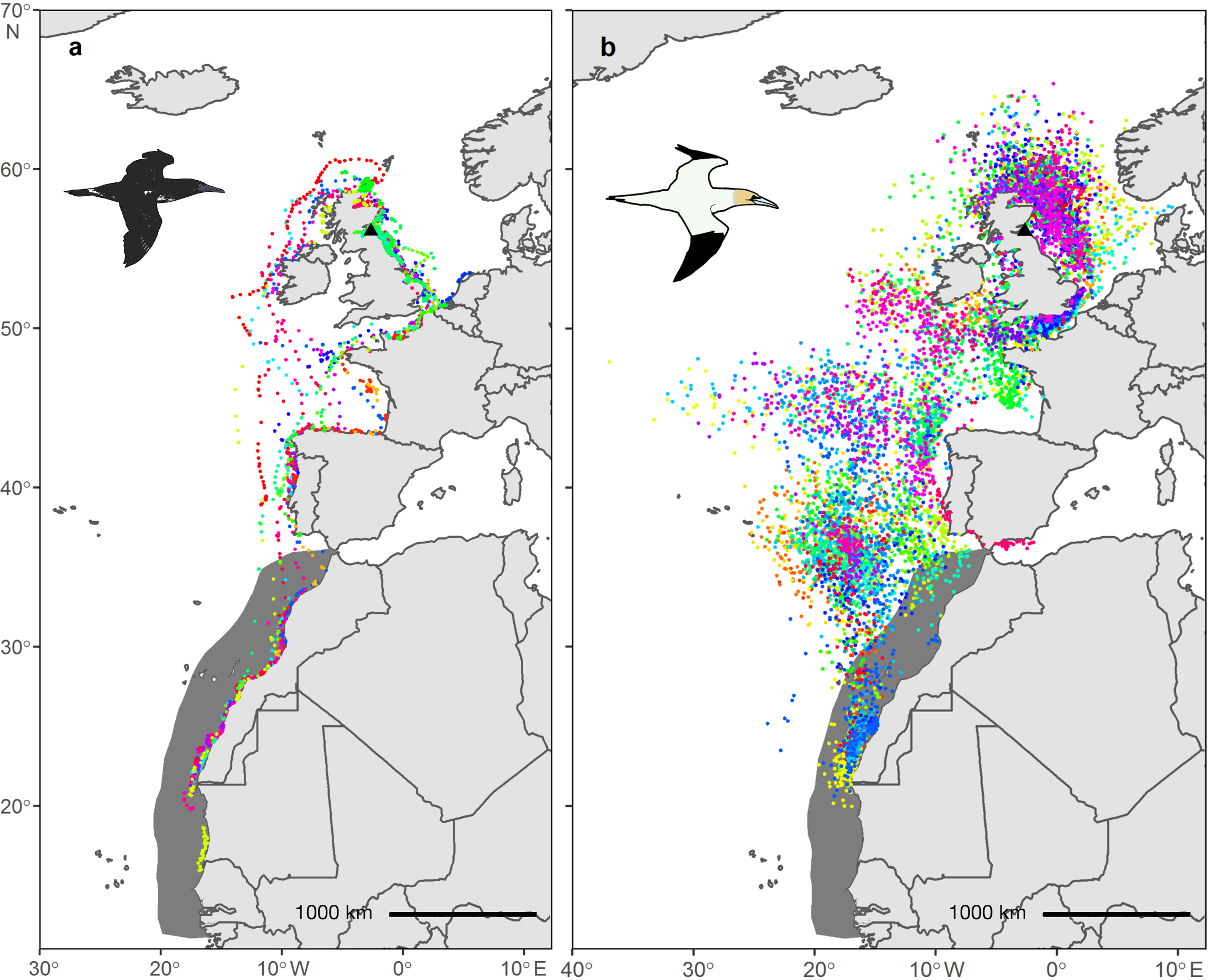

Forty-two juvenile northern gannets from the world’s largest colony, Bass Rock, Scotland, were equipped with solar-powered Argos-GPS PTTs in 2018 and 2019. In the same years, sixty-two adults were equipped with light-intensity geolocators.

Fledging dates for juvenile gannets were estimated using distance from the colony and travel speeds. The time taken and distance covered were estimated between the northern North Sea and the Strait of Gibraltar. This in order to compare migration speeds of juveniles and adults whilst taking into account different migration goals (some birds travelled further south than others).

More info about animal tracking with Argos

More coastal and more direct routes, but high mortality

Juveniles started their migrations slowly, spending up to 9 days drifting on the water before taking flight from the water for the first time. A similar flightless period has also been observed in juvenile wandering albatrosses. It seems that during that time they lose weight, allowing them to get airborne more easily.

Both juvenile and adult gannets travelled as far as the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem (CCLME) off the Atlantic coast of West Africa. During their journeys south, the juvenile gannets stayed closer to the coasts than adults and they travelled as many kilometres per day as the adults. Birds in each age group travelled around the British Isles in clockwise and counter-clockwise directions. The more direct routes taken by juveniles allowed them to reach the Strait of Gibraltar more quickly than adults.

Nearly a third of the juveniles died during the tracking period, most within a short period after fledging (tag data indicated the bird did not fledge or fly once fledged, there were multiple days of inactivity or a body was found), all during the first two months. Those birds showed more uncertainties in the direction they chose to migrate, making abrupt changes.

(a) GPS locations of 41 juvenile gannets tracked from Bass Rock (black triangle) between September and November 2018 and 2019; (b) Geolocator locations of 35 adults tracked from Bass Rock between September and January 2018−19 and 2019−20. Note that this technique is less precise with greater variance of the locations (but mean distance should not be biased). Individual birds are identified by colour. Shaded area shows the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem (from [Lane et al, 2021])

A potentially risky journey

The migration routes taken by gannets from Bass Rock pose a number of potential threats and obstacles. At the start of the journey the birds must negotiate a high and increasing density of offshore wind farms in the North Sea. At the end of their migration, the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem is an area of unregulated, unreported and illegal fishing activity. This fishing could threaten birds by depleting their prey but also the risk of by-catch, to which juvenile seabirds are more vulnerable (see also Tracking of juvenile grey-headed albatrosses or Argos helps in assessing fisheries bycatch risks to seabirds ). Wildlife conservation in this region should be a priority.

Reference and links

- Lane JV, Pollock CJ, Jeavons R, Sheddan M, Furness RW, Hamer KC (2021) Post-fledging movements, mortality and migration of juvenile northern gannets. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 671:207-218. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13804

- https://www.seabird.org/blog/juvenile-gannet-research

Photo: an adult (white-feathered) and a juvenile (dark-feathered) northern gannet (credit Maggie Sheddan)