← Back

Hudsonian godwits cross the windy ocean

The Hudsonian godwit is a migratory bird travelling a marathon, transoceanic flight from South America to Arctic or sub-Arctic North America. Their flight paths tracked using Argos, in relation with variable winds, can help understand how they travel such long distances.

Photo: a Hudsonian godwit equipped with an Argos PTT (credit: Natalia Martínez Curci)

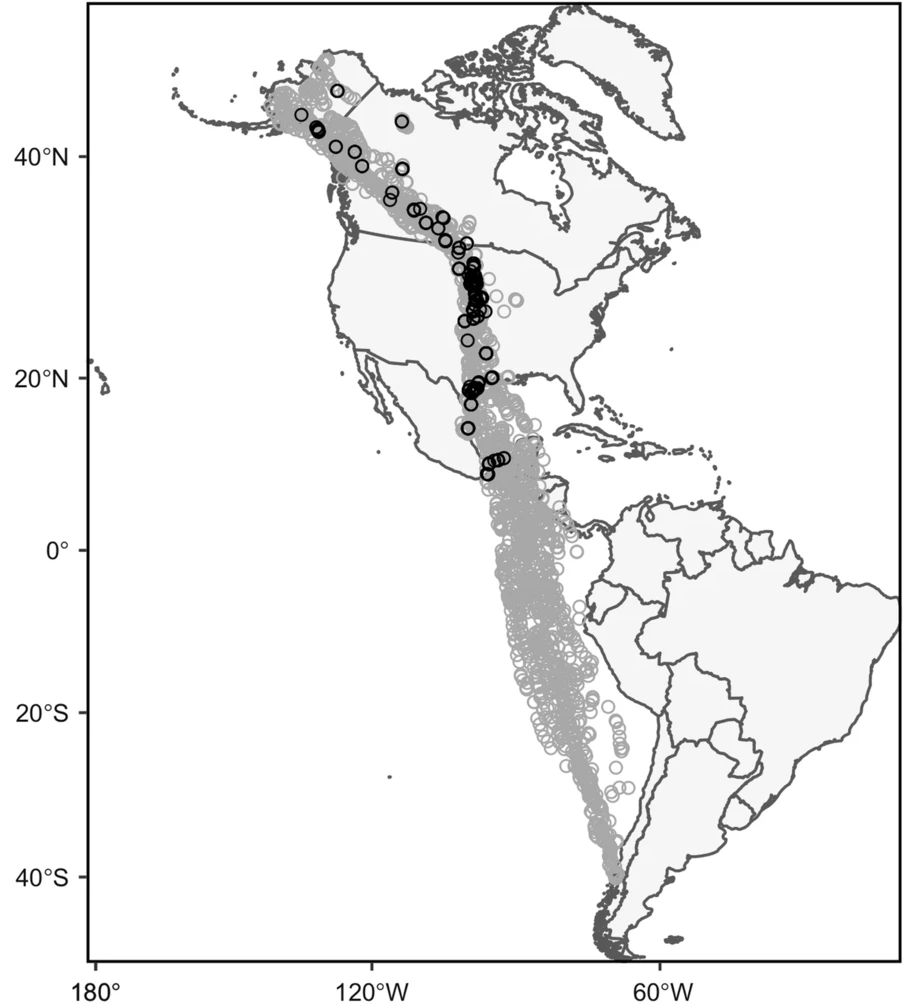

The full migration of the tracked Hudsonian godwits. The study examines the part between the start in Chile to the crossing of the Gulf of Mexico coasts (from [Linscott et al., 2022])

Hudsonian godwits (Limosa haemastica) are large shorebirds of the sandpiper family (see from the same family Juveniles black-tailed godwit tracked, Black-tailed godwits’ different migration behaviours). They breed in the far northwestern arctic and subarctic Alaska and Canada and migrate to South America in coastal Chile and Argentina. As for all migratory animals, managing efficiently energy costs is often the key to their successful migration. As birds, wind is one of the major environmental factors in their spending of energy, and different strategies have been recorded to face adverse winds without tiring too much.

The first part of the Hudsonian godwits’ migration towards Northern America takes place over open water – Pacific Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. It is made nonstop, lasting an average of about 6 days and traveling more than 8300 km, with few opportunities to stop. The winds they will encounter can’t be predicted from their starting point, as they cross different wind regimes (direction and/or strength) along the way. How do they manage their long-range travels in those conditions?

Tracking Hudsonian godwits and comparing their travels with winds

54 Hudsonian godwits were equipped with Argos PTT (25 Argos only, 29 with GPS) in Chiloé (Chile). A number stayed around and did not migrate. From the ones which did, 24 complete and 5 partial northward migratory tracks from Chiloé to the northern Gulf of Mexico coast were recorded. Two individuals were followed for three years.

More info about animal tracking with Argos

Winds at different altitudes were retrieved from the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 climate reanalysis dataset. The tags did not record any altitude information, though. Wind support, a quantity depending on the direction of travel and on the wind vector, was considered to be the best predictor of altitude during continuous flights.

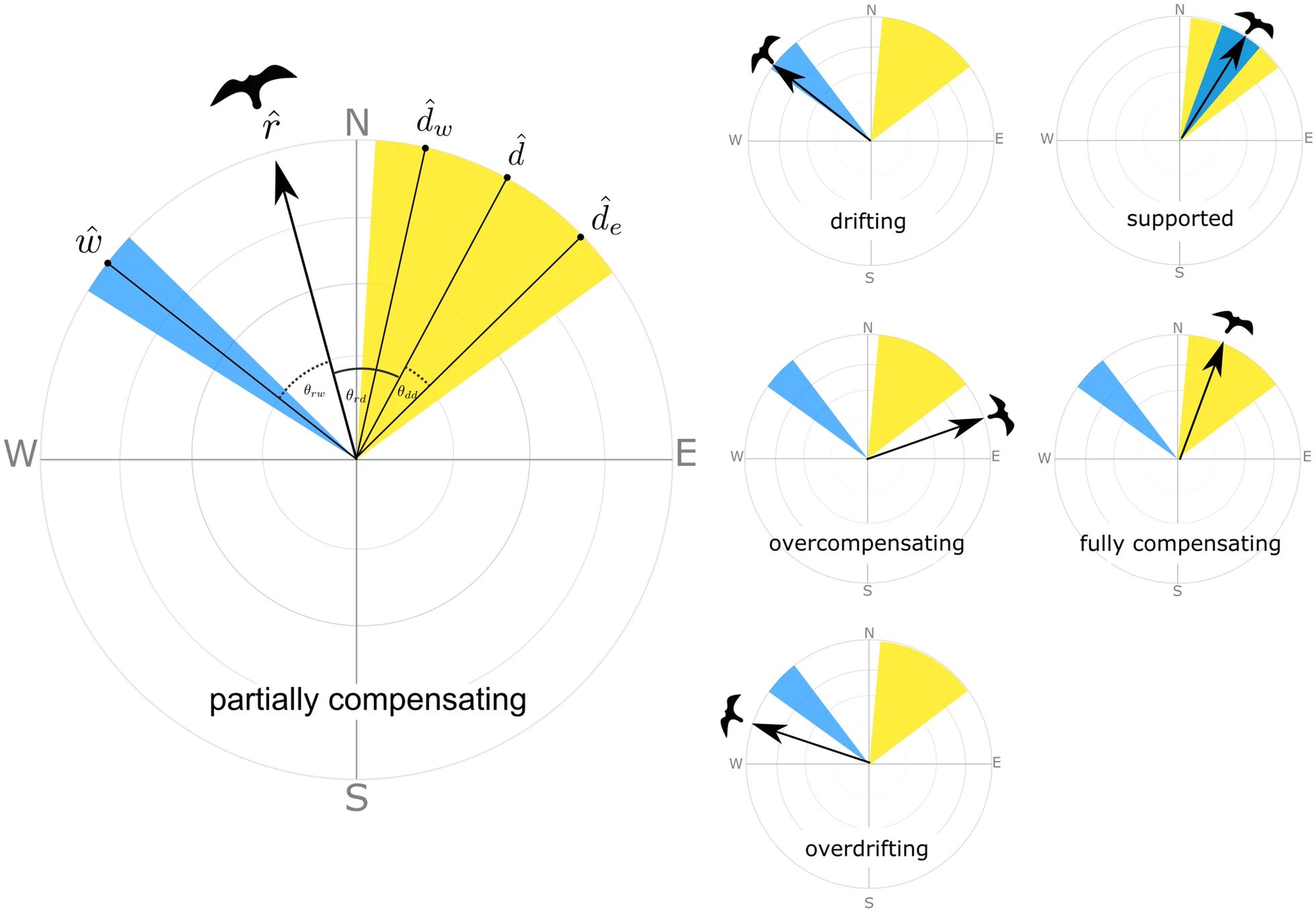

In blue the wind flow direction, in yellow the birds’ preferred direction, in black their actual direction of flight, for the different behaviors expected with respect to winds. (from [Linscott et al., 2022])

Several tactics have been recorded from birds facing adverse winds. They can adjust their heading and airspeed to fully (or ‘completely’) compensate for lateral displacement. They can also partially compensate, drift, and/or overcompensate. The expectation was that Hudsonian godwits would start by drifting, and especially drift over the open ocean, but increase compensation when approaching North America, relying then on some landmarks. It was also thought that their point of arrival on the Gulf of Mexico coasts would be influenced by wind conditions.

Monitoring wind regime shifts

The data showed that the Hudsonian godwits compensate more than they drift, even at the beginning of their long travel. The winds at the beginning of their travel may be selected for their departure, but they don’t condition it and they can leave under unfavorable winds. During their flight, they seem to stay within a given corridor, correcting when they were out of it. At the other end of their ocean crossing, the winds they encountered during migration did not seem to influence their landing point on the Gulf of Mexico coasts.

Differences were visible between individuals, and experience may play a role. However, if wind regimes changes, this may impact such migrants’ abilities. The predictions of such wind shifts may be crucial in Hudsonian godwits and similar migrant birds’ conservation.

Reference

Linscott, J.A., Navedo, J.G., Clements, S.J. et al. Compensation for wind drift prevails for a shorebird on a long-distance, transoceanic flight. Mov Ecol 10, 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-022-00310-z