← Back

Guillemots chicks swim with their fathers in the currents

Guillemots are seabirds with an original departure from the nest. Once on the sea, they migrate with their father to autumn staging areas. Argos satellite telemetry helps in better understand this travel, and assess whether they use the currents, how long and where to they travel.

The Alcidae seabirds have different strategies to leave from the nest, from immediately after hatching to waiting for full body size. Among this family, though, three species (common and Brünnich’s guillemots, razorbill) leave the nest while not yet flying, by leaping from it, often in a cliff and swim, accompanied by their father.

The background reason for this early departure from nest might be that feeding their chick is too energy-consuming for the parents, which carry only one prey item at a time to their nest. However, if the departure is well documented, what happens next was nearly unknown.

A cliff with many common and Brunnich’s guillemots nesting (credit Hallvard Strøm, Norwegian Polar Institute)

More info about animal tracking with Argos

Tracking guillemots’ chicks

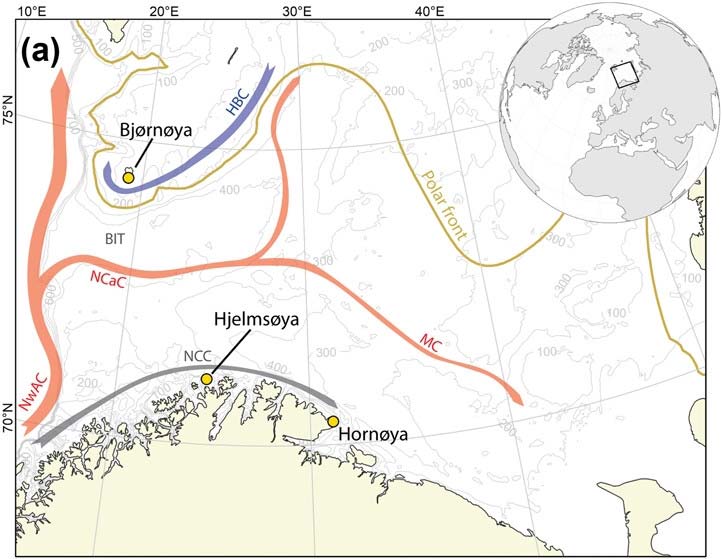

24 common guillemot (Uria aalge) and 10 Brünnich’s guillemot (Uria lomvia) chicks were captured in the nest at the end of the chick-rearing periods at Bjørnøya (74°21′N, 19°05′E), the southernmost island in the Svalbard Archipelago, in the southwestern Barents Sea. To assess the movements of father and chick after leaving the nest, the 34 chicks were equipped with satellite-linked Argos 5-g PTTs.

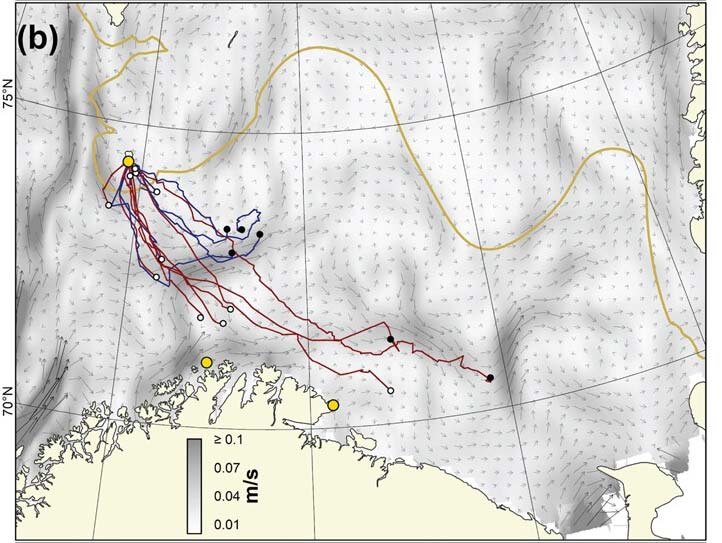

To determine whether the father & chick pairs are using ocean surface currents, and if so if they drift using them or swim actively, the tracks were compared with altimetry-derived geostrophic currents (Duacs products from Copernicus Marine Service). A model was used to assess if the tracked chicks adapted their swim with respect to the currents encountered en route. Ultimately, the tracking was used to assess where do they migrate.

Only half the tags transmitted data. Possible reasons for the loss are chick mortality during departure, antenna’s being damaged on the rocks of the breeding ledges, or tags falling off high cliffs or detaching from the chick during or shortly after jumping. Ten individuals were tracked for a least 10 days. The swimming migrations lasted 14 days for Brünnich’s guillemots and and 29 for the common guillemots, while the chicks are considered dependent for one or two months.

On departure, chicks (and their fathers) moved immediately away in a south–easterly direction, probably due to depleted resources close to the colony. The swim speeds after accounting for current speeds were in general double that of surrounding surface currents, showing that they do swim actively. At some point, they even had to cross the Hopen-Bjørnøya Current in a counter current direction, after which seven of the ten still tracked mostly swam along the currents (rather than taking the shortest route). The utilization of currents shows that the fathers must have spatial memory, to be thus aware of the existing flows.

The different individuals followed distinct migration paths and reached specific autumn staging areas that had previously been identified for adults for two the different species. Those areas, home to still dependent chicks should be protected from human disturbances.

This is all the more important given that the Bjørnøya guillemots’ swimming migration and autumn staging areas are on the border with, or upstream of, the most intensively developed and planned future hydrocarbon regions of the Barents Sea.

Reference & links

- Merkel, B. and Strøm, H. (2024), Post-colony swimming migration in the genus Uria. J Avian Biol, 2024: e03153. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.03153