← Back

Tracking plastic bottles from rivers to ocean

Plastic in the environment, especially in the ocean, is a major pollution concern currently. If it is well established that most of it comes from land through rivers, how far and by which path? A study using open-source Argos chipsets in bottles to track them tries to give an answer to this question.

A proof-of-concept study in the Ganges river basin

Ocean circulation models and current drifter buoys’ location data have been used to understand and predict how plastic pollution is moving and accumulating in the oceans (see e.g. Indonesia Chooses Space Technology in the Fight Against Pollution or Tsunami debris on the Pacific on Aviso website). However, buoys, if in plastic, are not similar in shape, weight and drogue to usual plastic litter. On their side, ocean circulation models include a number of assumptions that might not fit the case of plastic wastes.

The Ganges River system is one of the largest river systems in the world, with also a population of several hundred million people inhabiting the surrounding basin. Moreover, the use of plastic materials is increasing exponentially in India and Bangladesh. Among those plastic items, beverage bottles are among the most reported littered ones by the International Coastal Cleanup.

Track telemetry-equipped plastic bottles

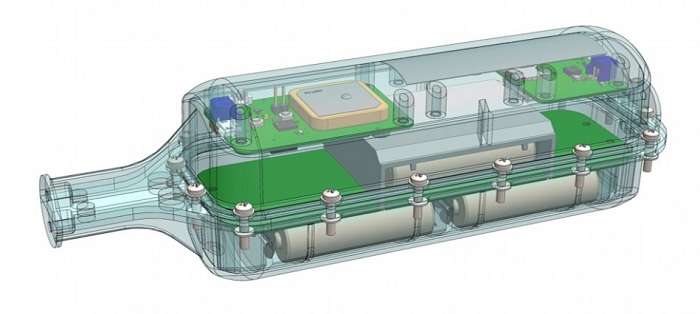

CAD image of the equipped bottles (crediArribada initiative)

During the National Geographic Sea to Source Ganges Expedition, a proof of concept study was undertaken by applying open source tracking technology (previously used on marine animals) to the tracking of plastic wastes. For this study, Plastic bottles were equipped with transmitters built using Arribada’s Horizon Argos ARTIC R2 developer’s kit, to get a more accurate idea of how plastic litter travels through rivers to the open ocean. The study included two phases. The first phase was led with high-rate data emission (thus short-lived) before the monsoon.

The second one, led after the monsoon, was done with Argos satellite telemetry and lower rates emissions, for longer tracking including out in the ocean. Three of the latter bottles were deployed directly in the ocean, twelve on rivers. All the transmitters were small enough to make this feasible within a 50 cl plastic bottle (if chosen carefully for its stocky shape). They were also light enough so that the flotation line was about the normal one for such a container, while keeping all antennas upright and over water level.

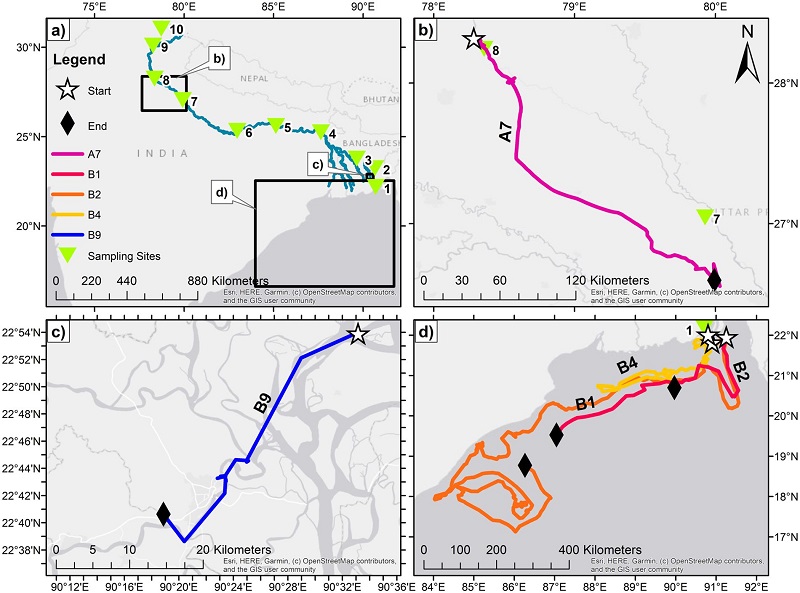

a:The map of the source to sea expedition and the study sites; b&c: example track of bottles deployed in rivers at site 8 and 9. And d, the tracks in the ocean only (bay of Bengal) (from [Duncan et al., 2020])

Tracking from rivers to ocean

40% of all bottles of the first phase appeared to become trapped or beached on a riverbank after deployment (after traveling an average of 72.2 km). This is probably in link with the low water levels on the rivers before the wet monsoon. The second phase bottles released in rivers encountered different problems, such as probable interactions with fishing and severe weather.

The three satellite bottle tags deployed at sea all took similar courses once they entered the Bay of Bengal. They moved in a westward direction close to the East Indian coastline, along the seasonal coastal current there. The longest track was of 2,844.6 km (B2 on the figure) and was tracked for 94 days (the longest time- period).

Use for a better knowledge

Such an approach can help to better understand the plastic pollution sources, movements and accumulation, and its impact on ecosystem. Additionally, possible impact on the people’s behaviours with respect to plastic items and plastic litters could occur through education and awareness opportunities.

Reference & links

- Duncan EM, Davies A, Brooks A, Chowdhury GW, Godley BJ, Jambeck J, et al. (2020) Message in a bottle: Open source technology to track the movement of plastic pollution. PLoS ONE 15(12): e0242459. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242459

- Arribada initiative website https://arribada.org/ & their Argos/Kineis Developer’s Kit https://arribada.org/horizon/

- https://www.facebook.com/emily.duncan.9849/videos/10164634770820066

- CLS Telemetry Website https://www.cls-telemetry.com/argos-solutions/argos-products/modems/artic-chipset/#1575449009767-35469d83-0ab9

Photo: Bottle released in the water (credit Heather Koldewey)