← Back

Chinese and Japanese sparrowhawks fly over the East-Asian continent

Chinese and Japanese sparrowhawks are migratory raptors from East Asia. They migrate from Russia and China to Indonesia and other islands nearby. Understanding their migration routes, stopover sites and wintering grounds will help better protect them.

Chinese Sparrowhawks (Accipiter soloensis) and Japanese Sparrowhawks (Accipiter gularis) are small raptors living in Eastern Asia. They feed mainly on small invertebrates, frogs, lizards and small birds. They have been seen feeding on insects (cicadas) on their wintering grounds. They migrate between Russia/China/Korean Peninsula and the Malay Archipelago, going through Thailand on their way back and forth. They fly over the continent, using the “East Asian Continental Flyway” (while shorebirds like spoon-billed sandpipers use the “East Asian – Australasian Flyway”, more coastal).

Neither species is considered especially threatened, but the Chinese sparrowhawk seems in decline. Their habitats are more and more modified by humans (forests replaced by palm-trees in Indonesia, in particular).

Tagging Chinese Sparrowhawks and Japanese Sparrowhawks

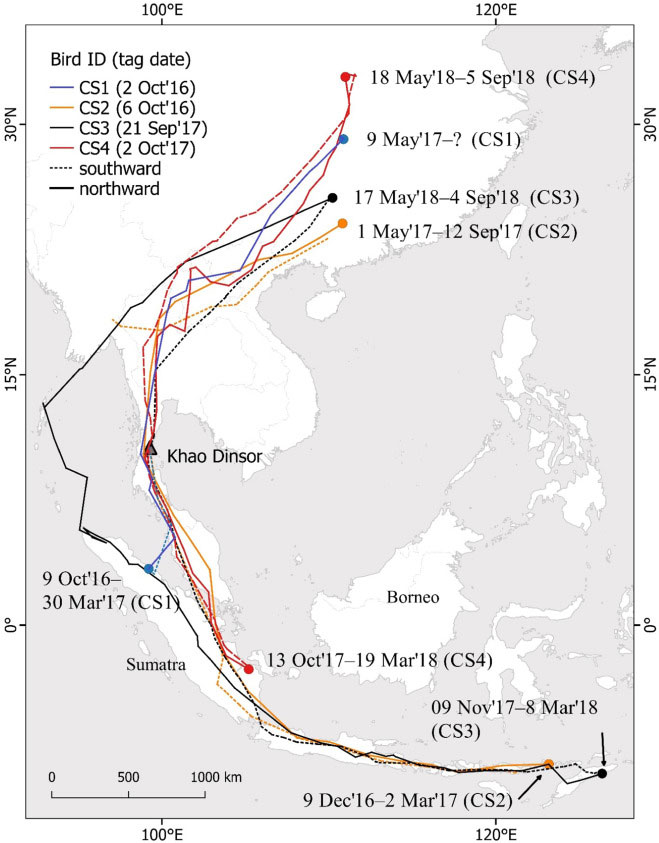

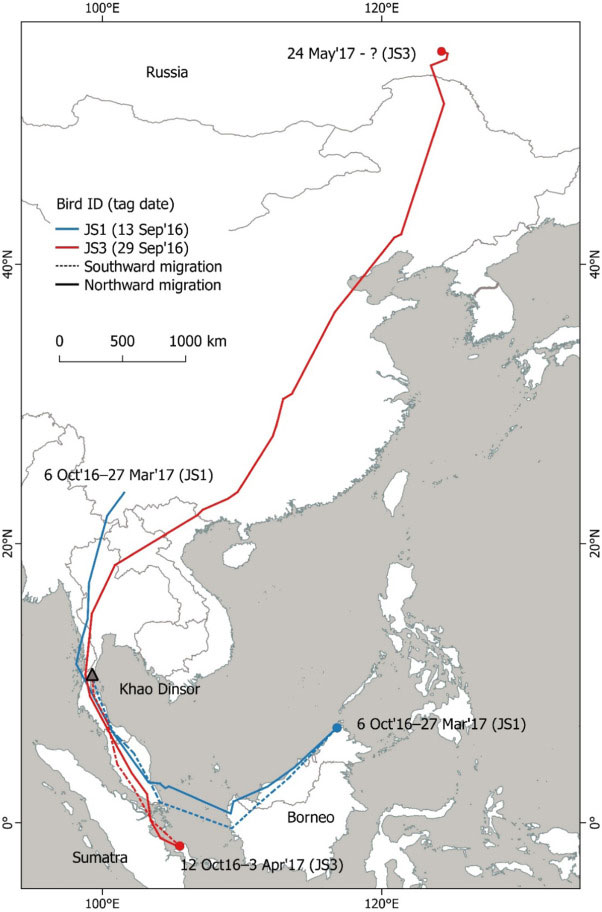

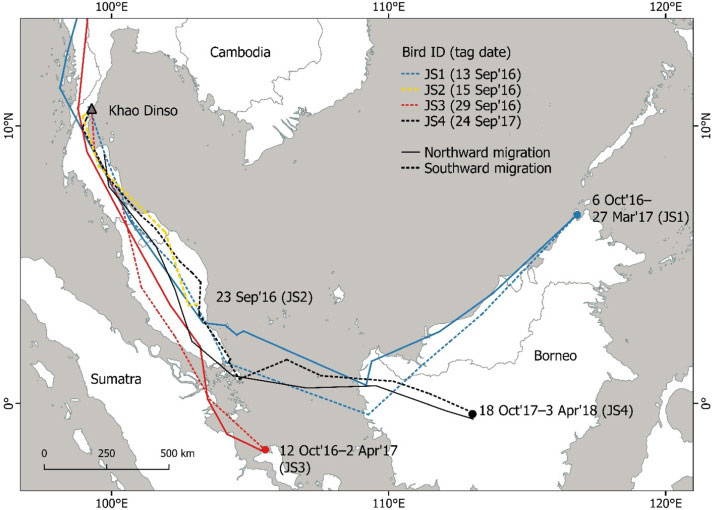

Four Chinese Sparrowhawks and four Japanese Sparrowhawks, all females since they are larger, were tagged with 4.5-g solar-powered Argos PTTs. The tagging took place during September–October 2016 & 2017 on their southward passage through southern Thailand at Khao Dinsor (Chumphon province, Thailand). There, over 150,000 Chinese and around 20,000 Japanese Sparrowhawks are seen on their southward migration each autumn.

Seven of the tagged birds reached their winter quarters, which covered a 3,000-km wide east-west spread from Sumatra to Timor-Leste. There, few data were received, probably since they kept under the canopy, where the solar battery couldn’t charge enough. They spent between 84 and 173 days there within areas of less than 23 km² (except one that covered over 600 km2), before heading northward to their breeding grounds. Data were transmitted for at least part of the northward journey for the seven birds. Moreover, two Chinese Sparrowhawks’ tags transmitted for part of a second year, enabling tracking of one full migration cycle totalling 14,688 (CS3) and 9,694 km (CS4).

Migrations of Chinese and Japanese sparrowhawks

Contrary to many raptors which take the shortest oversea path, both species seem to cross the ocean over significant distances. One of the tracked birds even did it by night. It must be noticed that some Chinese Sparrowhawks have been seen as far as Guam or Palau in the Pacific Ocean, or Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean.

Chinese Sparrowhawks wintered at Sumatra, East Nusa Tenggara and Timor-Leste before returning to Southern China around February to May. One Japanese Sparrowhawks spent 130-170 days in Sumatra and Borneo, before returning to Amur Oblast in Eastern Russia. Japanese Sparrowhawks made fewer stopovers on northward migration than Chinese Sparrowhawks. But no significant differences were found within or between species, in the daily distances flown during southward or northward journeys. Day-to-day distance varied widely for a given individual, though — up to around 800 and 382 km for Chinese and Japanese Sparrowhawk, respectively. Time spent on breeding grounds of Chinese Sparrowhawks were similar, 111 to 135 days, but migration and wintering durations varied widely due to the variable distances apart of their wintering grounds.

More tracking to understand Chinese and Japanese sparrowhawks

To have an understanding at the population level, more tracking than the present study will be necessary, ideally including males, too, using lighter tags. Tracking other raptor species following the same migratory path – the “East Asian Continental Flyway”—would also enable to better characterize the behaviours, including the differences between species, ages etc.

The fact that some of the identified stopover sites have been transformed from forest to agricultural lands is a major concern. The threats over the East Asian Continental Flyway and the migratory birds which fly it need to be addressed for conservation purposes.

Reference and links

- Andrew J. Pierce, Chukiat Nualsri, Kaset Sutasha and Philip D. Round, Determining the migration routes and wintering areas of Asian sparrowhawks through satellite telemetry, Global Ecology and Conservation, (2021) doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01837

- https://www.biodconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/8.-Mr.-Andrew-J.-Pierce.pdf

- https://www.nstda.or.th/en/news-related-to-research/research-news-year-2019/890-study-of-raptors%E2%80%99-migration-route-helps-promote-species-conservation-and-eco-tourism.html

Main Photo: A Chinese Sparrowhawk in flight (credit A. J. Pierce)