← Back

How many Mediterranean migrating eels are eaten on their way to the Atlantic?

Analysis of migrating eels’ tracks can provide with estimate of the rate of predation on them. It seems that half of the migrating silver eels released on the French Mediterranean coast can be consumed by marine mammals before reaching the Gibraltar Straight. Assessing such natural threats to an endangered species could help in better management.

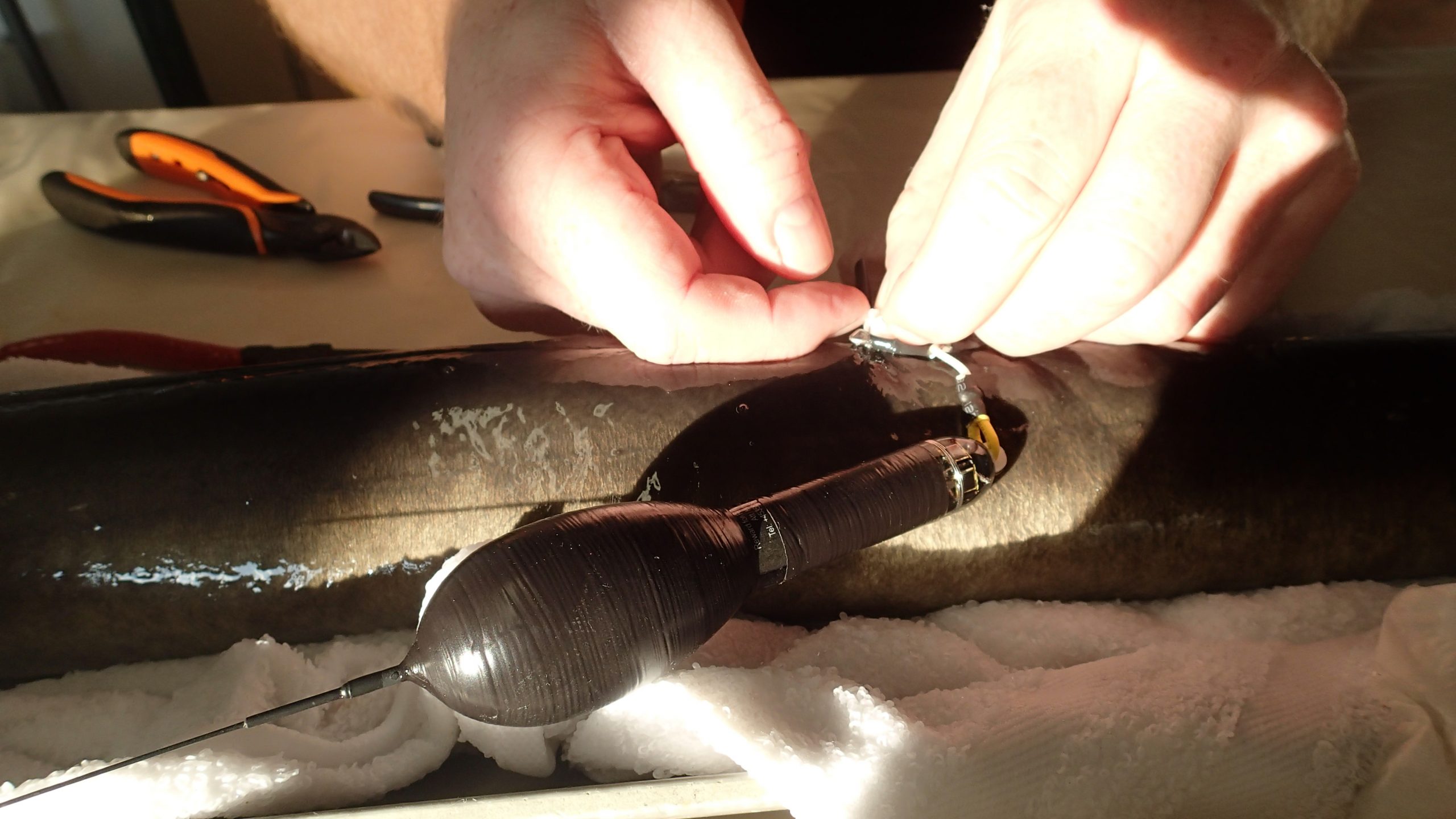

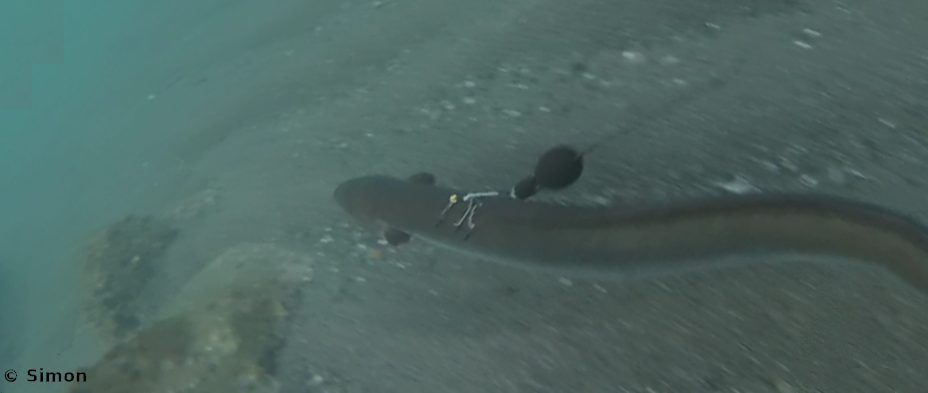

Photo: An eel in the sea with a pop-up tag (Credit G. Simon, Perpignan University)

The European eel (Anguilla anguilla L.) continental phase is distributed across the majority of coastal countries in Europe and North Africa. The southern limit is in Morocco (30°N) and the northern one in the Barents Sea (72°N). It is also spanning around all of the Mediterranean basin coasts. The European eel is listed as a critically endangered species in the IUCN Red List. In particular there was a rapid decrease of its stock in the 1980s. Glass eel recruitment (its post-larval juvenile phase) is currently at its lowest level. In 2020, it was down to 1 to 7% with respect to 1960-1979 reference average.

We already mentioned studies using eels’ tracking to better know this species’ migration from the Mediterranean Sea (see Eels’ travel in the Mediterranean tracked thanks to Argos & goniometer and Eels’ travel in the Atlantic tracked by Argos satellite telemetry). We mentioned that no eels released from the Mediterranean have yet been tracked all the way to the Sargasso Sea. It is also true for eels released from other parts of Europe. This is due in part to tag batteries and programmed duration before release. But some eels seem to have been eaten, too, on their way towards mid-Atlantic. The scientists went back to the eels’ tracking data to have a closer look at those predation events.

Hints that a tracked eel have been predated

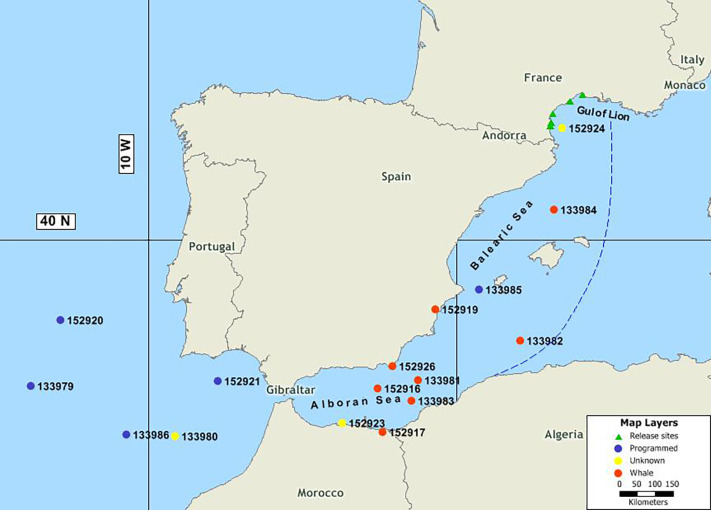

Nineteen eels were tagged with pop-up archival satellite tags (PSAT) and released in the Gulf of Lion, northwestern Mediterranean Sea in 2013 and 2015-16. Tags were programmed to pop-up after six months in 2013, eight or ten months in 2015-2016.

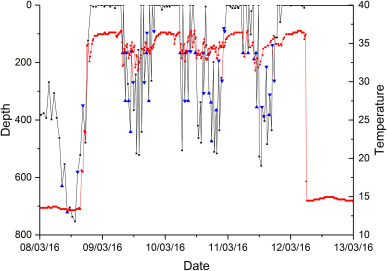

The hints indicating a predation of an eel are sharp rises in temperature (when by marine mammals, which internal temperature is higher than 30°C, well above the sea water temperature) and/or in depth or maximum daylight level changes (indicating predation either by marine mammals or ectothermic animals such as sharks). Frequent visits to the sea surface afterwards is also consistent with predation by a marine mammal. The stop of the eel diel vertical migration cycle is also a way of detecting such events.

More info about animal tracking with Argos

Depth and temperature recorded data for a predated eel tag. Depth data in black, with squares showing measured depth and blue triangles showing the values estimated and recorded by the tag when vertical movement rate exceeds the ability of the tag to record a measured value. The red line shows the temperature. Note the alternating foraging and rest periods, visible both in diving activity and stomach temperature (from [Westerberg et al., 2021])

A high rate of eel predation by marine mammals in the Mediterranean Sea

On the sixteen tags which transmitted data, a predation was observed for nine eels (56%). Among those, eight occurred in the Mediterranean Sea. One was in the Atlantic, from the five eels reaching this ocean.

In the Mediterranean Sea, most (75%) of the eels that were eaten were taken at the depths these fish occupy during the day (450 to 700 m), which was unexpected. Those depths are supposed to offer a refuge from predation, since visual detection is not possible there. However, deep divers that use biosonar will still detect prey in such darkness.

The records of the tags after predations in the Mediterranean show clear hints of marine mammals: temperature increasing above 30°C, regular surfacing… Moreover, the maximum depths reached and the dive cycle duration point towards toothed whales – either sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus, most probably for five eels, Cuvier’s beaked whales (Ziphius cavirostris) or long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas). Most predation events in the Mediterranean Sea (7 out of 8) took place in the Alboran or south Balearic Sea. A hypothesis is that the migration path of the eels is funneled there along a narrow corridor towards the Gibraltar Strait, while some cetacean species congregate there annually to feed.

In the Atlantic Ocean, only one predation event was detected (on 5 eels recorded on having reached it). Contrary to the Mediterranean, it was on the continental shelf (but the narrowness of the shelf in the Mediterranean Sea might be why it was never the case there). The tag temperature record hints of an ectothermic animal, like a shark.

Release (green triangles) and pop-up positions of the 19 tagged eels from the 2013 and 2015-16 studies. The dots show the end positions corrected for drift of all the tags, colour-coded according to the estimated reason of this ending. (from [Westerberg et al., 2021])

Assessing the proportion of eels reaching the Sargasso Sea

If the results of this study are representative, 50% of the migrating silver eels from the Mediterranean Sea are lost while passing the Alboran and Balearic Seas. To this day, the proportion of eels that are able to contribute to spawning is completely unknown. Assessing such predation along the migration path should help in this estimate.

More tracking would be necessary to better assess the mortality rate of Mediterranean eels by predation, and finally the rate of those reaching spawning grounds. This information would be important to improve stock management of the European eel.

Reference

H.Westerberg, E.Amilhat, M.Wahlberg, K.Aarestrup, E.Faliex, G.Simon, C.Tardye, D.Rightong, 2021: Predation on migrating eels (Anguilla anguilla L.) from the Western Mediterranean, J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Eco., 544 (2021), 151613, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2021.151613