← Back

Tracking of juvenile grey-headed albatrosses

Albatrosses are iconic seabirds of the Southern Ocean. Argos satellite telemetry has greatly increased knowledge of the at-sea distribution and behaviour of adults, and contributed to initiatives aimed at reducing their bycatch in fisheries. However, much less is known about movements of juveniles and immatures, which are potentially at higher risk in areas unused by adults. BAS is tracking juvenile grey-headed albatrosses from Bird Island to fill this knowledge gap and help mitigate the associated threat.

Albatrosses are a textbook case for demonstrating the conservation application of satellite-tracking data. They can stay at sea for months at a time, never landing on solid ground, traveling incredible distances and their movements are thus impossible to follow other than by tracking. The development of the Argos system enabled scientists to discover a great deal about their feeding areas. It quickly became apparent that incidental mortality (bycatch) in fisheries was a major concern (the albatrosses drowned on fish hooks, or broke wings colliding with trawl cables). Argos tracking data helped in better defining areas used in the breeding and nonbreeding seasons where mitigation measures should be used, so as to lower seabird bycatch rates. However, most tracking tags were deployed on adults, and only more recently has it become clear that juvenile and immatures seabirds may show very different foraging behaviours. They disperse further, possibly avoiding competition with adults and spend years at sea finding the best foraging grounds. Thus, they may encounter different fisheries where they are at greater risk of bycatch than the more experimented adults.

An open-ocean species

The grey-headed albatross (Thalassarche chrysostoma) is one of the most pelagic species of albatrosses, staying and feeding in the open ocean. It is listed as Endangered by the IUCN because of a very rapid decline of ~5% per year in recent decades at South Georgia (in the South Atlantic) which holds half the world’s population. As with all albatross species, they are long-lived and show markedly different behaviour depending on their age. Long-term monitoring of ringed birds found that fewer juveniles were re-sighted than expected, indicating a high rate of mortality between fledging and first return to the colony.

Giant petrels depredate young grey-headed albatrosses on their very first flight or a little later, when they are still close to their colony. Some mortality can also be attributed to climatic variation. In addition, observers on board fishing vessels reported seeing juvenile and immature grey-headed albatrosses bycaught in areas where adults were not usually recorded.

More info about birds tracking

Tracking for better knowledge

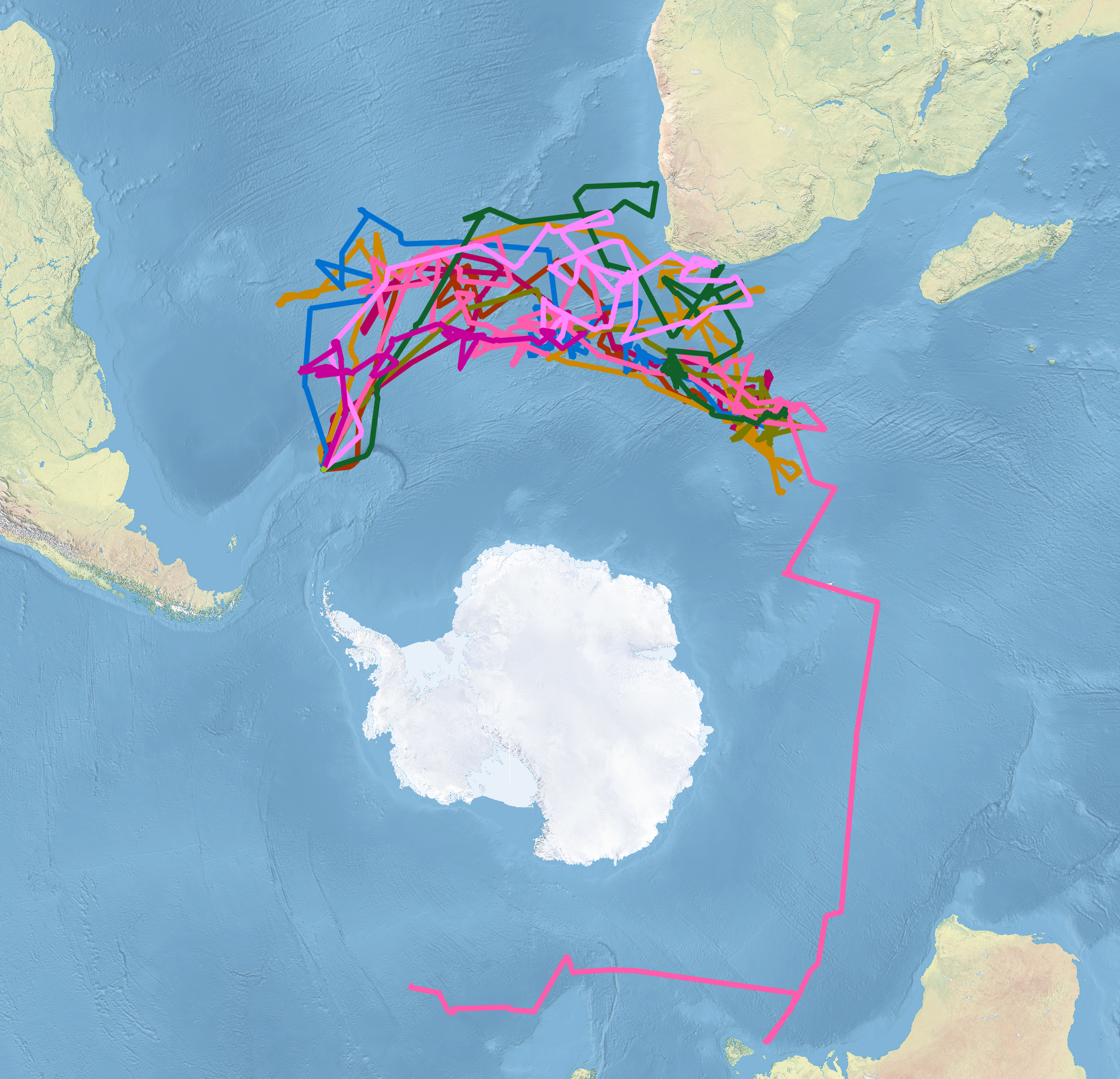

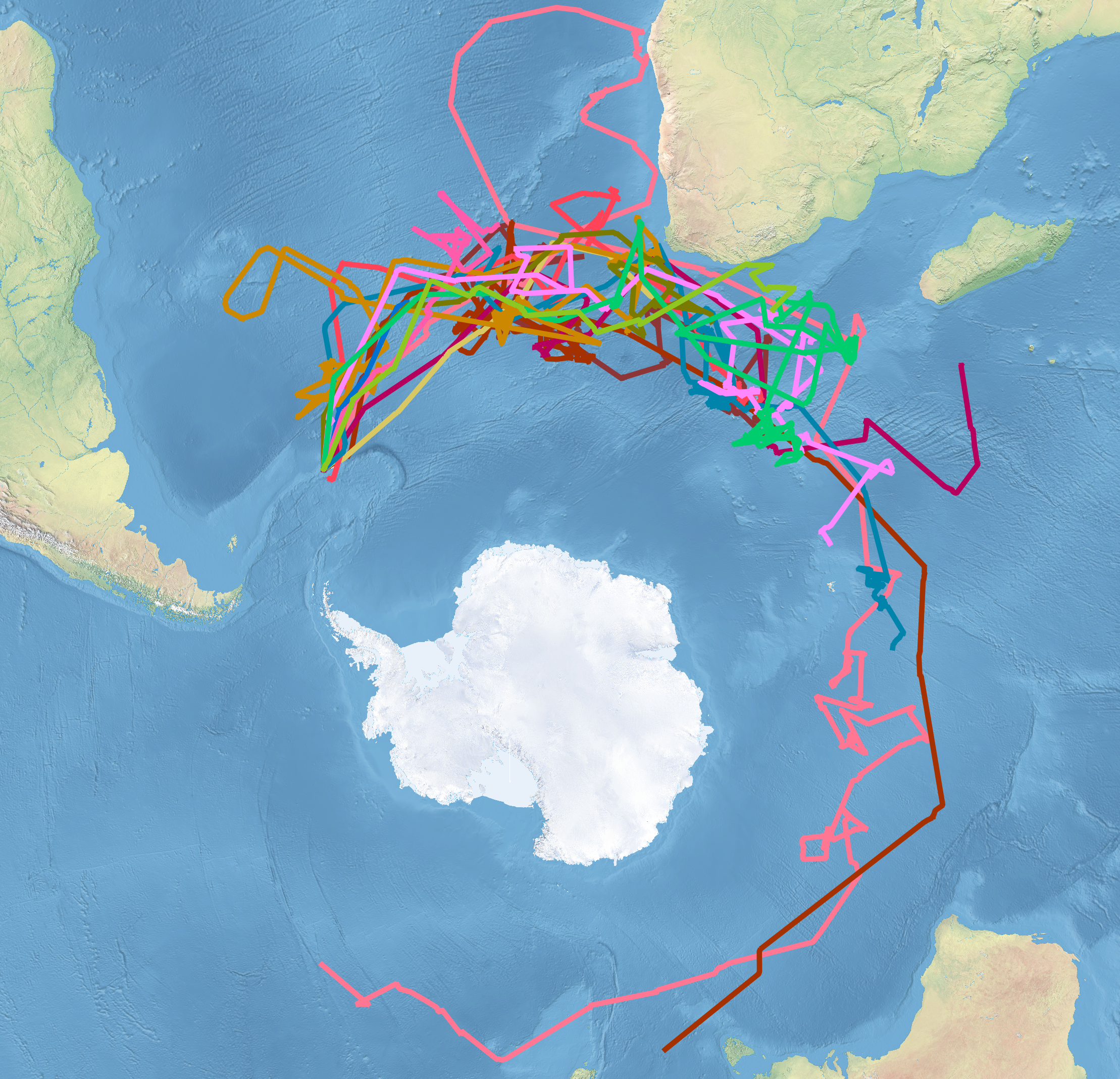

British Antarctic Survey and BirdLife International recognised that there was an urgent need to map the movements and foraging areas of juveniles in order to determine the overlap with fisheries, and to assess the survival rate in the initial weeks and months after they fledge. In May 2018, Argos PTTs were attached to 16 grey-headed albatross juveniles before they left Bird Island (South Georgia) with a duty cycle of 8 hours on and 43 hours off. One year later, 16 PTTs were attached to other chicks.

Funding for devices used in the 2019 season was obtained from the South Georgia Heritage Trust, and the Friends of South Georgia Island, and for those in the 2018 season from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, through the BirdLife International Marine Programme.

The foraging grounds of the juvenile grey-headed albatrosses in the months after they fledged overlapped with tuna fleet fishing areas in the central South Atlantic. This overlap occurs in their first few months at-sea, when young birds are particulaly vulnerable to bycatch due to their inexperience/naïve scavenging behaviour. This finding proves that bycaught birds likely originate from South Georgia, and that reducing bycatch in these fleets may help halt their population decline.

An awareness-raising campaign has been launched in the Asian countries which are the flag states of these fleets. Moreover, the information has been presented to ICCAT (International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas) for consideration by the fisheries.

The juveniles covered huge distances, with the tracks showing how far even young birds can fly – some individuals flew more than 50 000 km (i.e. more than the Earth’s circumference at the Equator) in just a few months.

Links & references

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/albatross_stories/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Albytaskforce/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/AlbyTaskForce

- Page on RSPB website: https://community.rspb.org.uk/getinvolved/b/albatross-stories/posts/behind-the-scenes-of-grey-headed-albatross-tracking-filling-knowledge-gaps

- Page on BAS website: https://www.bas.ac.uk/project/grey-headed-albatross-juvenile-tracking/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/bas_news

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/BritishAntarcticSurvey

- YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/AntarcticSurvey

Photo: A grey-headed albatross chick with an attached PTT (the aerial can be seen coming from the back of the bird). (credit Derren Fox)