← Back

Common nighthawk populations do not stay apart during migrations

The common nighthawk is an American migratory bird, traveling long distances between North America and Tropical South America. For their conservation and understanding, biologists study if their different populations remain separated, or if they mix at some places(s) or time(s) during their migrations.

The common nighthawk (Chordeiles minor) is widespread in the Americas, from Canada to South America. It is a declining, insectivorous, long-distance migratory bird.

As for most migratory animals, one of the questions is to determine if the populations always go back and forth each on their sites, or if they mix at some place or time during their migration (see also e.g. Gull-billed terns keep their migration route and winter sites from year to year or Pronghorn migration across borders and human-made landscapes). Migratory connectivity is a measure of this. High connectivity means that the different populations are dissociated and may evolve differently. Low connectivity means that they mix more, and may be influenced by the same factors. This knowledge of migratory connectivity is important to understand what is influencing the population trajectory and evolution of a given species.

Get more information about animal tracking with Argos

Tracking common nighthawk populations along migrations

Ninety-four captured birds, both male and female, over 70 g and without injuries were tagged with 3.5-g GPS-Argos tags. Data from fifty-two individuals were analyzed for migratory connectivity. They covered twelve different breeding populations, encompassing at least one complete migration with a stopover around Mississippi,

The capture locations in North America (and 100 km around) were defined as breeding grounds. The wintering grounds were defined as the furthest points from breeding, mostly to the east in the Amazon and Cerrado biomes of Brazil.

Similar migration routes

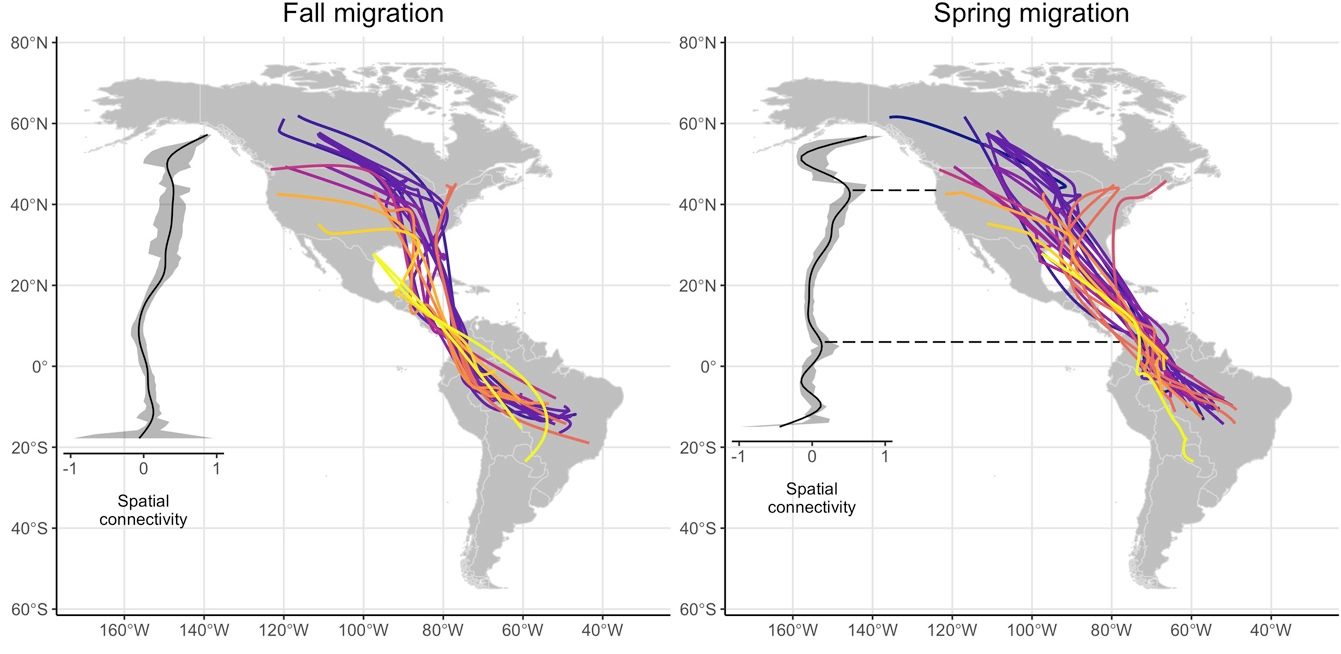

Migration routes for the twelve common nighthawk breeding populations (color-coded) tracked during fall and spring migration. The routes are very similar. (from [Knight et al., 2021])

Statistical analyses were led in both space and time to determine the correlations between the locations of the birds. From those analyses, male/female differences seemed to be negligible overall concerning migratory connectivity. Results show that whatever the breeding population and wintering grounds, the global migration route is the same. All tracked common nighthawks flew over the Gulf of Mexico (never over land through Mexico) and across the Amazon basin for fall migration. They went roughly back for spring migration. In fall, individuals migrated towards the Central/Mississippi flyway and along the Colombian Andes. When coming back they went from Colombia’s northern coast over the Gulf. After crossing it, they dispersed towards their breeding grounds.

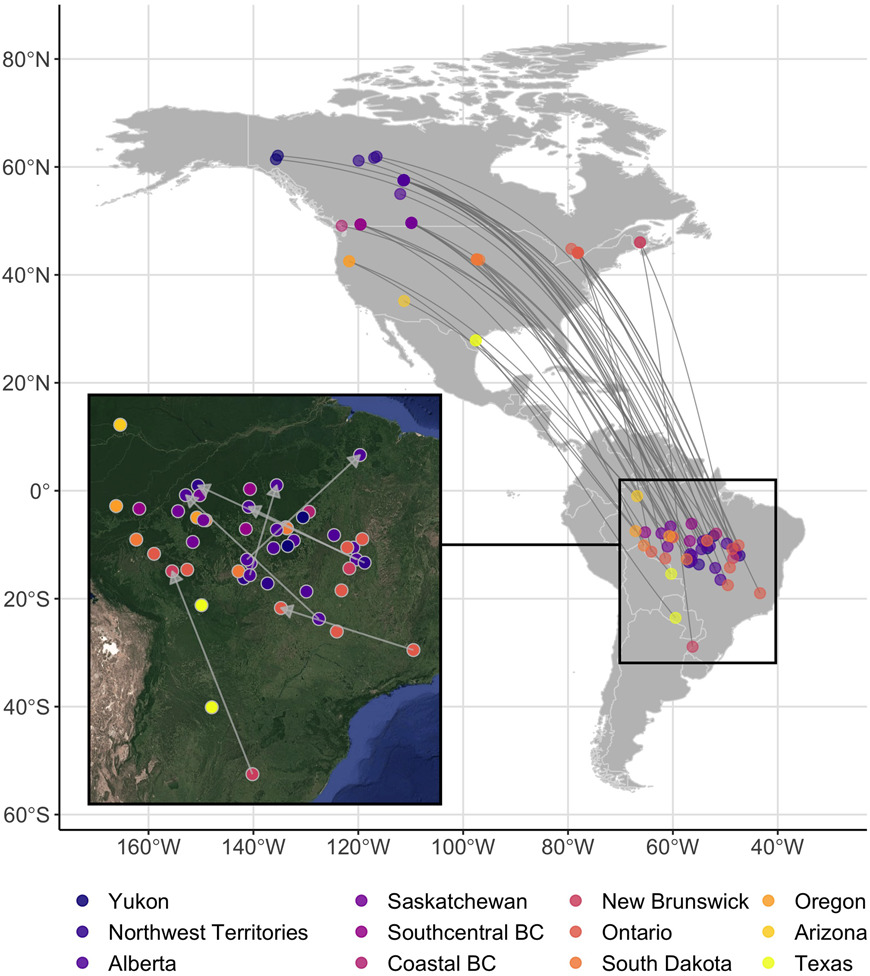

Breeding sites and wintering sites for the populations tracked (color-coded). Inset: 7 birds relocated during their wintering. There is no or few grouping by breeding sites on the wintering sites, showing that they mix (low connectivity) (from [Knight et al., 2021])

Mostly low migratory connectivity

The wintering grounds are not shown as population-specific. The migrated birds are spreading all over the area without any clear correlation from their breeding grounds (low connectivity). The area in Colombia where they cross the Andes, in particular the Magdalena River Valley, represents a migratory bottleneck. There, nighthawk population could negatively be affected at the species level. All in all, mostly, the common nighthawks show low migratory connectivity in South America.

There are a few times and places with higher separation. Firstly when entering the northern Amazon region on fall migration, which could create population-specific pressures through threats like habitat loss and pesticide use. Then in South America before crossing back the Gulf of Mexico on spring migration when the winds can change the chance of reaching the other side for the birds. And, lastly, in North America, both leaving and coming back to the breeding grounds.

Help in directing conservation action

The common nighthawk migrations seem thus not to be population-specific during most of the annual cycle outside of the breeding grounds. A few key points or key times were however pinpointed by the study. The use of a full annual cycle (breeding, fall migration, wintering, spring migration) is important in such analyses, to identify places and times that can limit populations.

Such an approach could be applied to other long-range migrating species. This can help in directing conservation action, since the analysis gives potential causes of differential population trends.

Reference

Knight, E.C., Harrison, A.‐L., Scarpignato, A.L., Van Wilgenburg, S.L., Bayne, E.M., Ng, J.W., Angell, E., Bowman, R., Brigham, R.M., Drolet, B., Easton, W.E., Forrester, T.R., Foster, J.T., Haché, S., Hannah, K.C., Hick, K.G., Ibarzabal, J., Imlay, T.L., Mackenzie, S.A., Marsh, A., McGuire, L.P., Newberry, G.N., Newstead, D., Sidler, A., Sinclair, P.H., Stephens, J.L., Swanson, D.L., Tremblay, J.A. and Marra, P.P. (2021), Comprehensive estimation of spatial and temporal migratory connectivity across the annual cycle to direct conservation efforts. Ecography. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.05111

Photo: a common nighthawk on a tree branch, by day (credit Jukka Jantunen)