← Back

Adelie penguin movement analysed in three dimensions

Adelie penguins live and breed around Antarctica. As with all penguins, they forage in a three-dimensional environment, ranging horizontally at-sea and diving vertically to capture prey. A recent study analysed the relationship between horizontal and vertical movements, and how movement behaviour is influenced by environmental conditions.

The Adelie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) lives around the Antarctic coastline and is one of the most studied polar seabirds on the planet. Because of their krill-dominated diets and strong association with the sea-ice environment, they are considered a key indicator species by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR).

Béchervaise Island in East Antarctica (67°35 S, 67°49 E), nearly due south of Kerguelen Islands, is an Adelie penguin nesting site. It is home to over 2000 breeding pairs and has been part of a long-term monitoring program led by the Australian Antarctic Division.

Adelie penguin foraging behaviour and habitat have been the focus of numerous studies. However, most studies have only examined one aspect of movement, analysing horizontal and vertical movements separately. When looking at their horizontal tracks, in theory, areas where penguins spend the most time are assumed to be important foraging habitats. In reality though, these foraging assumptions may not reflect how foraging occurs within a complex three-dimensional environment.

Tracking and modelling 3D movements

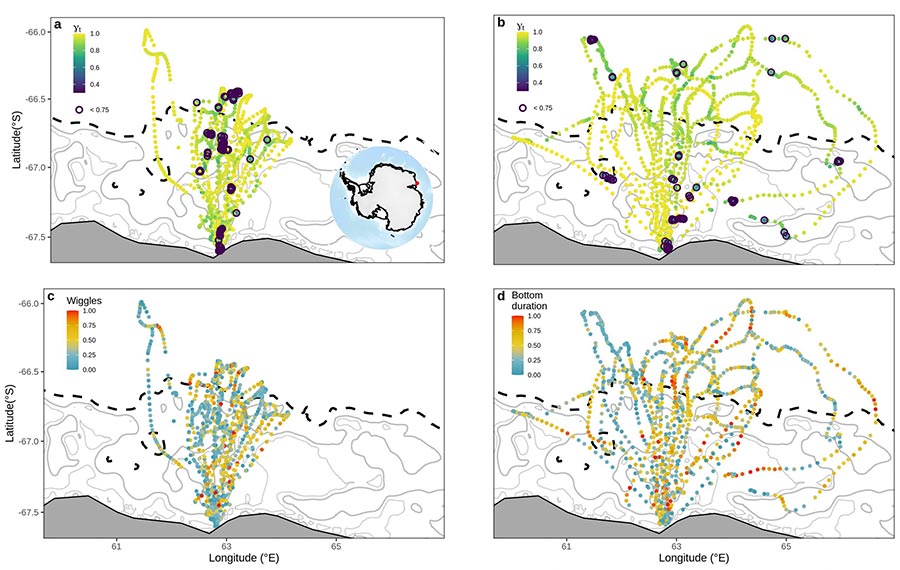

To test these foraging assumptions, a recent study used data from 23 Adelie penguins (13 females, 10 males) from Béchervaise Island equipped with two different tags over six breeding seasons. One tag located the penguins (classical Argos PTTs: horizontal movement), the other recorded their dive data (archival tag time-depth recorders: diving information). Foraging movements were examined during the two different stages of the chick-rearing period: guard and crèche.

The guard period (late-December to mid-late January) is when both parents take turns to care for their chicks, making short (less than 60 km) and alternating foraging trips. During the crèche period (mid-January to early mid-February), the chicks no longer need to be kept warm by parents. Both parents are free to forage simultaneously, and must do so to acquire enough food for their growing chicks, travelling further from the colony (up to 125 km).

For the 23 individuals, horizontal movements were processed using state-space-models (SSMs). In total, 2220 horizontal locations were recorded, with 38,845 dives spread across these locations. The integration of horizontal and vertical movement provided a three-dimensional overview of penguin foraging activity. This allowed the researchers to examine where the penguins were going, and where diving activity was concentrated.

Underwater diving behaviours at each location were examined using various measurements, such as the number of undulations in the dive profile and the time spent around the maximum dive depth. Environmental data (bathymetry, sea ice concentration, sea surface temperature, sea surface height) were also extracted at each location to examine how three-dimensional movements vary in relation to environmental conditions.

Analysis of moves in 3D

Penguin movement behaviour was markedly different during the guard and crèche period. While penguins rarely went beyond the continental shelf during guard, they ranged more widely in crèche, travelling further east and west and foraging north of the shelf break.

Contrary to what is traditionally believed, the penguins did not spend the most time in discrete prey-patches along their horizontal movement track. Instead, penguins dived continuously over the course of their foraging trip. This could mean two things. Penguins at this colony in East Antarctica may forage within a region of consistent high prey availability. Alternatively, opportunistic foraging wherever they find prey may be more practical and less risky for these penguins who are under intense pressure to capture enough food to feed their chicks.

In addition to these behavioural findings, when their chicks were small (guard stage), penguins seemed to prefer foraging in environments with lots of sea ice and a steep sea floor. It’s believed these two environmental features interact to enhance nutrient and prey concentrations. During the crèche phase, sea ice concentration is substantially decreased and the area is almost ice-free. At this time, penguins appeared to target areas with shallow and warmer surface waters.

The findings of this study are important because they provide a better understanding of the foraging behaviour of Adelie penguins, and in doing so, challenge our understanding of how foraging habitat can be identified for this iconic Antarctic predator.

Reference and links

- Riaz, J., Bestley, S., Wotherspoon, S. et al. Horizontal-vertical movement relationships: Adelie penguins forage continuously throughout provisioning trips. Mov Ecol 9, 43 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-021-00280-8

- This work was supported through the Australian Antarctic program.

Main Photo: An Adelie penguin with an Argos PTT (© Louise Emmerson/Australian Antarctic Division)